There is no proof of a calamity for life on Earth similar to the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event (The Great Dying), 252 million years ago. For both the Ordovician and Devonian Extinctions, land plants were partially responsible for unbalancing the chemistry on which life relied on, but these two unfortunate events have both worked against and in favor of a revolution for both fauna and flora. The Great Dying was radical, unmerciful and cataclysmic, and unlike any prior extinction event, it was the planet acting against the life that had animated it. The maelstrom of events emerging from beneath Earth’s crust ended the almost 300 million year of the Paleozoic (538.8 to 251.9 million years ago), for the dawn of the Mesozoic (251.9 to 66 million years ago). But there is no revolution without collateral victims, and no cataclysm without a reverberating aftermath. The first 50 million years of the Mesozoic almost never seized to lay outside the ominous shadow of disaster, and while most caved under the harsh geological challenges of the Triassic, some became victors and would rule the Earth for the rest of an era known by everyone as The Age of Dinosaurs.

(-> Read more about The Great Dying here: https://astropeeps.com/2022/09/27/the-great-dying/)

(-> Read more about The Ordovician Extinction here: https://astropeeps.com/2023/05/21/ordovician-extinction-or-how-the-first-terrestrial-plants-almost-killed-all-life-on-earth/)

(-> Read more about The Devonian Extinction here: https://astropeeps.com/2023/09/22/the-devonian-extinction-no-clear-culprit-for-a-great-disaster/)

*

Triassic Planet

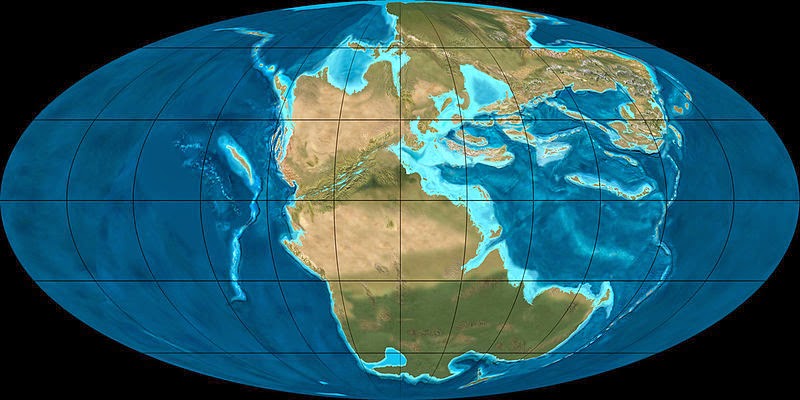

The eruption of the Siberian Traps, covering an area larger than today’s Kazakhstan, for more than half a million years, anoxic and sulfidic oceans and a global temperature of 42° C left Earth devastated. It might have been an easier journey for life to recover if geological conditions were different. During Permian, the two massive continents, Laurasia and Gondwana drew closer together, with Gondwana shifting to the north, until the two collided into a massive supercontinent: Pangaea. At the beginning of The Triassic Period, Earth was covered by a massive ocean (the Panthalassic Ocean) and a C-shaped continent extending from the South to the North Pole. Throughout the entire Triassic, Pangea slowly rotated anticlockwise, to the north, widening the Tethys Ocean, third largest ocean on Earth. Almost enclosed by land, the Paleo-Tethys Ocean, second largest, after the Panthalassic Ocean, began shrinking as South China moved toward north, following the same motion of Pangaea, into a future collision with North China.

The Siberian Traps had spewed a volume of a kilometer in depth of lava during the Permian-Triassic Extinction. Once it finally stopped erupting the climate had little to almost no help to recover. A continent spreading from pole to pole made it impossible for oceanic currents to circulate around the globe. Inland Pangaea remained mostly dry and barren, while its coasts were constantly hit by violent monsoons. Global weather remained hot for most of the Triassic, with a mean oceanic surface temperature of 32° C. To put it into perspective, on July 31, 2023, the Copernicus Climate Change Service logged a record breaking global sea surface temperature of 20.96° C, the highest we have ever witnessed. The highest, we, humans, have ever witnessed.

Climate throughout the Triassic was not linear, but abrupt, with spikes in temperatures and sudden global cooling. The gargantuan eruption of the Siberian Traps at the end of the Permian had released catastrophic amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere. At the very dawn of the Triassic CO2 levels were nearly 21 times higher compared to today. During the next million years (251 to 250 million years ago), it dropped constantly. However, tropical sea surface temperatures remained at around 38° C. On land there was not much difference between the poles and subtropical areas, while arid land extended to high altitudes. A stagnant ocean divided by a massive continent could not cool down the northern and southern most latitudes efficiently. By the end of Early Triassic (251.9 to 247.2 million years ago), global temperatures cooled down by 6° C, but even so, the planetary climate remained very warm.

The Middle Triassic (247.2 to 237 million years ago) witnessed various episodes of global cooling followed by brief spikes. Still not enough for Earth to exit its greenhouse phase, but enough for life to recover and diversify again, after the End-Permian cataclysm and the hostile Early Triassic.

Up until Late Triassic (237 to 201.4 million years ago), little to no rain could reach inland Pangaea, therefore it remained mostly a vast desert almost devoid of plants and animals. For the first three million years, climate continued cooling. But once more, disaster was just around the corner. Plate tectonics were constantly shifting, stretching and putting pressure on the supercontinent. Pangaea was about to split into a configuration that would finally lead to the continents we know today. And when plate tectonics drift apart, volcanism intensifies.

Three million years into the Carnian (first stage of the Late Triassic), the Wrangellia Traps (modern Alaska, Yukon and British Columbia in Eastern Canada and Washington State) started erupting. Though significantly smaller than the Siberian Traps, the Wrangellia Traps erupted for 6 million years, amounting to a 6 km deep layer of lava deposits. Global temperature spiked by 3 to 6° C and CO2 levels rose to more than 1800 ppm (parts per million) compared to today’s 420 ppm. Yet this time, the consequences were surprisingly different. Since the Wrangellia Traps were far smaller than the Siberian Traps, and the eruption, though far more durable, was less violent, the spike in global temperature turned out to be less radical. Water started evaporating, cumulating in clouds. Water vapor is a greenhouse gas, therefore, the more the clouds, the less efficient the ability of the planet to cool down by releasing heat back into the cosmos. It started raining. And it rained for 2 million years. Everywhere on Earth. The Carnian Pluvial Episode was in itself a minor but global extinction event. Oceans acidified, marshes and wetlands that had disappeared during the Permian appeared all over the land, plants grew taller in an attempt to reach for light and most animals that had adapted for so long to feeding on small shrubs, and living in arid conditions disappeared. The Carnian Pluvial Episode lasted between 234 to 232 million years ago, and by the time the Carnian geological Stage ended (227 million years ago), Earth was under the footprints of a new ruler. But we’ll discuss about that later.

(-> Read more about the Carnian Pluvial Episode here: https://astropeeps.com/2022/12/22/the-carnian-pluvial-event/)

When the Carnian ended, the Wrangellia Traps cooled down, and for the next 26 million years, during the last two stages of the Late Triassic, Norian and Rhaetian, Earth saw an almost constant decrease in temperatures. Large ice caps appeared in the arctic circle and at high latitudes, Pangaea finally split and started a long process of fragmentation, and oceanic currents were no longer stemmed by a supercontinent.

And in its very final stage, 201 million years ago, temperatures suddenly spiked into the dramatic global warming of the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction.

*

Triassic Plants and Animals

Not much is known about Early Triassic plants. The Permian-Triassic Extinction Event had wiped out most of the fauna on Earth. The once abundant glassopterids, seed-like ferns with umbrella-shaped sporophylls, were still present, but had retreated to the wetter climate near the coasts. Flora, in general, became fragmented as equatorial and tropical temperatures were very inhospitable, and coastal to continental differences were radical.

There is little evidence up until Middle Triassic for a clear image of what plants looked like, or how they evolved. However, by 247 million years ago, flora began to reclaim the land, mostly in the northern hemisphere, where we find large coal deposits reappearing after a five million years’ global gap. One plant that had successfully managed not only to survive The Great Dying, but actually to benefit from it and from the Early and hostile Triassic, was the globally spread pleuromeia, with its unbranched trunk, the height of a human adult, with grass-like leaves at its top. Being a distant relative to the clubmosses of the Carboniferous (358.9 to 298.9 million years ago), it had the ability of storing large quantities of CO2 while also regrowing its leaves at a fast pace, therefore being resilient to the high temperatures in both humid and arid areas.

Starting with the Middle Triassic, ferns and cycads evolved to a more complex aspect, spreading all over the land, and successfully surviving the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, becoming dominant throughout the Jurassic. Conifers diversified and became widespread, mostly in the northern hemisphere, but were still relatively short.

Following the Carnian Pluvial Event, fibrous plants took over the world. Conifers started growing up to 10 m in the northern hemisphere, while in the south dicroidium evolved from a shrub-sized fern to a 5 to 30 m tall seed bearing plant.

This new generation of plants raised an issue for most animals. They became too tall, with leaves far beyond the reach of most ground-based crawlers, that were no longer able to feed on them.

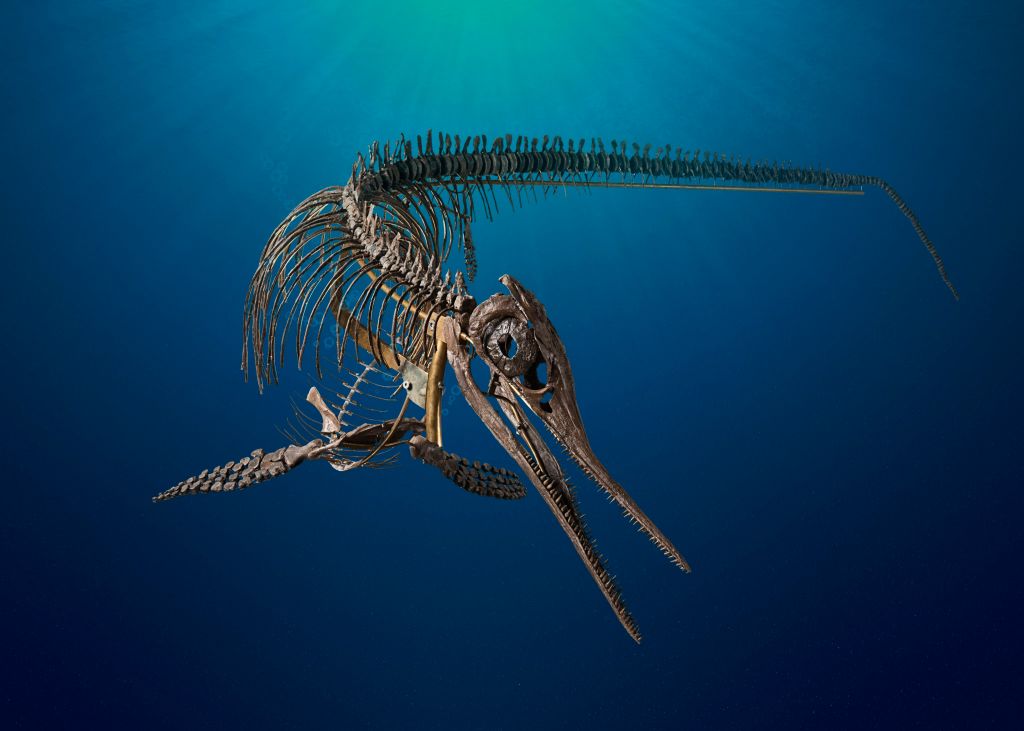

In the ocean, the trilobites had forever vanished following, the Great Dying. So did all corals, ammonoids, most gastropods, fish and everything else that had populated the waters up until the extinction event. Bivalves, cephalopods, bryozoans and brachiopods slowly recovered by Mid Triassic, and crinoids with their array of arms and central feeding fan spread all over the shallow ocean floor.

The clade of synapsids first appeared during the Carboniferous. During the Permian, they became most likely to rule the land. Yet, both mammalian and none-mammalian synapsids almost went extinct during the Great Dying. The gorgonopsids and dimetrodons, virtually at the very top of the food chain, never reached the Triassic. The lystrosaurus, was one of the very few synapsids to walk into the Early Triassic, but soon after it went extinct. In fact, only the very small survived, evolved and adapted. By Mid Triassic the thrinaxodon had appeared. Unlike the lystrosaurus, that resembled a broad-headed lizard, the thrinaxodon’s legs were more efficiently supporting the underpart of a body now covered in short-haired fur. The animal no longer walked like a lizard, but had evolved to a more articulate and fluid mammal-like walk. And as Triassic was closing to an end, the very first true mammal appeared: the morganucodon. This animal was covered in a fully developed fur, had sharp front teeth, excellent hearing and sense of smell, and… was the size of a thumb. Talking about underdogs, mammals were doomed to stay in the dark for many millions of years, hiding underground and constantly fearing great predators. And while the Chicxulub asteroid was their chance of emerging as rulers of the Earth for the past 66 millions of years, so was the series of disastrous events of the Triassic a chance for the rise of the new rulers of the Mesozoic: the dinosaurs.

*

The Triassic Underdog

The Permian had been animated by life. The first reptiles and synapsids came to being, populating the lands around water bodies. Saber-toothed gorgonopsians, dimetrodons and dicynodonts, of various sizes and dietary habits lived side by side with archosauromorphs, ancestors of the crocodiles, dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Amphibians ranged from very small to giant creatures, surpassing a metric ton in weight. There is an abundance of fossil records and footprints of these animals up to the Late Permian, and then… nothing. The Early Triassic looks barren, fossil record becomes rare, and footprints disappear. Under the shadow of death of The Great Dying nothing seems to be able to cling to life, except for very small reptiles and synapsids, that had radiated to a sufficient extent to survive the Permian-Triassic Extinction.

Two million years into the Early Triassic, a new creature, though only 30 to 50 cm tall, and up to 1 m long, emerges on the still very inhospitable lands of our Planet. The prorotodactylus was a novelty among creatures. First of all, unlike previous reptiles, it walked on its hind legs, leaving a digitigrade mark, meaning only the toes supported the weight of the animal. Their front limbs were more articulate, with the fifth digit being separate from the rest. Similar to a human hand, the third digit was longer than the rest, with the following digits becoming progressively shorter. The three middle digits of their hind limbs were closer together, compared to lizards, where all five digits are spread apart from one another and the animal uses both tarsals and metatarsals for support. Prorotodactylus hind legs are also closer together and support the abdomen, rather than being located on each side of the body.

The amount of possibilities of movement, hunting and agility were unprecedented. The first protodinosaur had emerged.

The environment was slowly recovering, and the archosaurs were starting to radiate into two major groups. Both these groups managed to survive to present day. First, there were the pseudosuchia, meaning false crocodiles, ancestors of modern suchia, commonly known as crocodiles. Some of them became very successful predators, such as the proterosuchus or the parasuchus, of the phytosaurs group, that could grow up to 2 m, and would evolve to reach giant lengths of 5 to 6 m during the Late Triassic. The second group was the avemetatarsalia divided into pterosaurs and dinosaurs. Pterosaurs were partially covered in feathers, would walk on their hind limbs, sometimes aiding the support of their body weight with their articulate front winged limbs that were mainly used for flying and gliding. Pterosaurs had thus become the first vertebrates in Earth’s history to fly. Ironically, birds have no relation to pterosaurs, but are our own modern dinosaurs, as they have evolved from this second group of the avemetatarsalia, the dinosauromorphs.

To speak about proper dinosaurs before the Late Triassic would be an overreach. Early and Middle Triassic dinosauromorphs were rapidly evolving, but were not proper dinosaurs yet. If the prorotodactylus was only the size of a dog, come Middle Triassic, dinosauromorphs grew to more than twice the size. Their hind limbs became stronger, and would no longer need the use of their front limbs for walking or support. Their upper body skeleton became broader with more developed muscles and more articulate and complex joints attached to the humerus bone, allowing them to grab and attack. Their cranial chamber became wider and their jaws acquired a formidable strength, with an array of new, more developed muscles and a more articulate maxillary. The giant amphibians and lizards that had dominated land and water were bound to crawl the ground. Furthermore, both these groups were and still are cold blooded, therefore they rely on specific climates and environmental conditions. But just like their distant and modern relatives, the birds, dinosauromorphs, and the later dinosaurs, were warm blooded, would walk upright, be agile and far more intelligent.

Thus, when the Carnian Pluvial Episode, with its 2 million years of rain (234 to 232 million years ago), started, dinosauromorphs were given the chance to evolve into proper dinosaurs and truly become the most successful land animals on Earth. Constant floods and lack of light pushed flora to adapt to new conditions. Shrubs and ferns disappeared or became taller. Trees increased in size, while their leafy tops became beyond the reach for all lizards and amphibians that were no longer able to properly feed on them. As entire groups of herbivores became extinct, so did the predators relying on hunting this plant eating animals. Dinosauromorphs, however, evolved alongside these new type of trees and ferns, and grew to ever larger sizes. Being warm blooded, they adapted easily to the extreme weather of the Carnian Pluvial Episode, and by the time the rain had stopped, well into the Late Triassic, dinosaurs were already roaming the lush and green lands of a supercontinent that was about to break into a dramatic global extinction event.

*

The Triassic-Jurassic Extinction

There is little to no certainty to what exactly has caused the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event, 201.4 million years ago. Everything related to it seems contradictory to a very large extent. Entire genera in both sea and on land were forever wiped from the face of the Earth. Corals, conodonts, large amphibians, most archosaurs and ichthyosaurs became extinct, yet plants, the remaining archosaurs, such as crocodilians, dinosaurs and pterosaurs, not to mention mammals, seemed to remain unaffected, almost thriving during and following the extinction event. Oceans acidified and oxygen levels dropped dramatically in some parts of the world, while in others, oxygen levels became even more abundant. Global temperatures rose by 6 to 9° C, yet there are short cooling episodes and there is strong evidence for sudden drops in sea levels and mild glaciations. The Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event is still puzzling, and not theory related to it seems to fully explain what exactly happened or why so many animals went extinct while many others benefitted from it.

The Triassic in itself was a long, mostly passive extinction event: The Permian-Triassic Extinction Event had left Earth almost devoid of life, with a giant supercontinent that prevented life to recover at a fast pace; the climate was either extremely dry or severely wet, with monsoons hitting the coasts unend; the violent 6 million yearlong eruption of the Wrangellia Traps triggered The Carnian Pluvial Episode, with its 2 million years of global rain, followed shortly by a global cooling episode.

On a cosmic related level, there were also several impactors that collided with Earth during the Triassic, but none to cause the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event. The Manicouagan Reservoir, located in Quebec, is the largest impact crater of the Triassic, with a diameter of 137 km and a maximum depth of 350 m. The asteroid that hit the planet was around 5 km in diameter. There is proof of an ejected blanket from Earth’s crust, with deposits of quartz, thousands of kilometers away from the impact point. Yet, the collision happened 214 million years ago, 13 million years before the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event, and there is no evidence that it had dramatically affected life on our planet.

In comparison, the Chicxulub Crater is 180 km in diameter, but 20 km in depth, while the culprit, the asteroid that hit Earth, is three times larger in diameter compared to the Manicouagan Reservoir impactor.

There are other shocked quartz deposits that have been discovered in France, Italy and North Dakota towards the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, but none significant enough to have caused any sort of extinction.

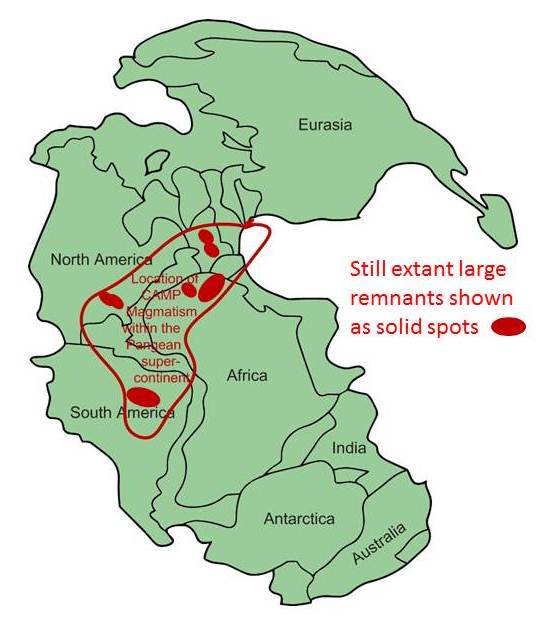

During the entire Triassic, the supercontinent Pangaea had stretched continuously, thinning the crust of the planet to a breaking point. Africa, North and South America were still conjoined, but were about to break apart. North America was pushing north, while, South America and Africa, still part of Gondwana, was pushing south. Spreading upon the rift between them, the massive Central Atlantic magmatic province (CAMP) reached the tipping point and started erupting. There is no record in our entire planet’s history for the quantity of CO2 emissions in such a short period of time as for those released by CAMP during the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event, 201.4 million years ago. One sole volcanic emission released more CO2 than the entire mankind over the 21st century. And there were thousands of eruptions, spanning on a territory the size of the modern South American continent. The volcanic activity came in irregular pulses for more than 600.000 years. When the first eruptions occurred, in what is now Morocco, CO2 levels suddenly quadrupled from 1000 ppm to 4000 ppm. Oceans around the equator and tropics acidified, global temperature spiked and the climate became seasonal. It would stabilize later, during the Jurassic, to a more uniform humid and warmer weather, but fauna and flora were traumatized by the sudden change in global climate.

When the CAMP eruptions were finally over, the world had glimpses of what we can recognize today as modern continents. In the northern hemisphere, North America had almost separated from Gondwana to the south and from Europe to the east. Europe was still conjoined to Siberia to the north and was about to separate as an individual landmass later during the Jurassic. This proto-Eurasian continent, looked nothing like the one we know today, but had started rotating anticlockwise and moving to the east, very slowly opening the future Atlantic Ocean. In the southern hemisphere, South America, Africa, India, Antarctica and Australia were still conjoined in a giant Gondwana.

*

Triassic Underdog Turned King of the Mesozoic

Out of all five major extinction events, there is no other we can relate to more than the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction. Over the past century we have released tremendous amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere, and as a result our climate has become gradually warmer. 1 or 2° C might not seem much, but the increase happened over a century, not over 600.000 years, as is the case for the Triassic-Jurassic Extinction. We can already see organisms unable to survive an ever warmer climate, thus vanishing forever. Although we are globally affected by the climate change, the central belt of the Earth, between the two tropics is most severely affected by long droughts followed by violent oceanic weather episodes.

During the End-Triassic Extinction and the massive CAMP eruptions, life in the equatorial and tropical regions of Earth was faced with unbearable temperatures and weather condition, not to mention the toxic gases injected into the atmosphere by volcanoes. Mammals in the region, still very small, hid underground or migrated north or south. Crocodilians, with their thick skin, were resilient enough and could linger in shallow waters, but dinosaurs, so abundant in the CAMP region, needed to flee the disaster. They had already proven their incredible capacity to adapt and quickly evolve, following climatic trends during the Carnian Pluvial Event. It was now time for them to adapt to the cold of the lands they were forced to migrate to. Dinosaurs could no longer find enough vegetation between the tropics, so they roamed towards the poles, where vegetation was plentiful. As a result, they grew feathers to insulate their bodies from the lower temperatures and seasonal longer nights. Even more surprising, some dinosaurs, such as the plateosaurus, developed the ability to increase or decrease their growth rate. The environmental breakdown of the End-Triassic left dinosaurs with virtually no other predators, as fauna had been hit by an array of disasters for the past 32 million years. Dinosaurs had radiated into several groups, had adapted to various conditions and climates, had become stronger, more agile and efficient and highly intelligent, with exceptional cognitive abilities. And as plants grew taller, more fibrous and robust, in order to survive the sauropod herbivores, so did dinosaurs grow and diversify, in order to survive as well. Their adaptive features are one of the most successful in the entire animal world throughout our entire planet’s history.

The underdog of the Triassic had become ruler of the Earth, with at least 25 sauropod species, some dinosaurs easily surpassing 50 metric tons – such as the brachiosaurus –, while others – such as the allosaurus –, becoming some of our planet’s most rapacious predators.

Giants now roamed both land and sky.

The world was warm and humid. Past calamities had finally come to an end.

Triassic was a part of the past.

The Age of Dinosaurs had begun.

– Roman Alexander

Leave a comment