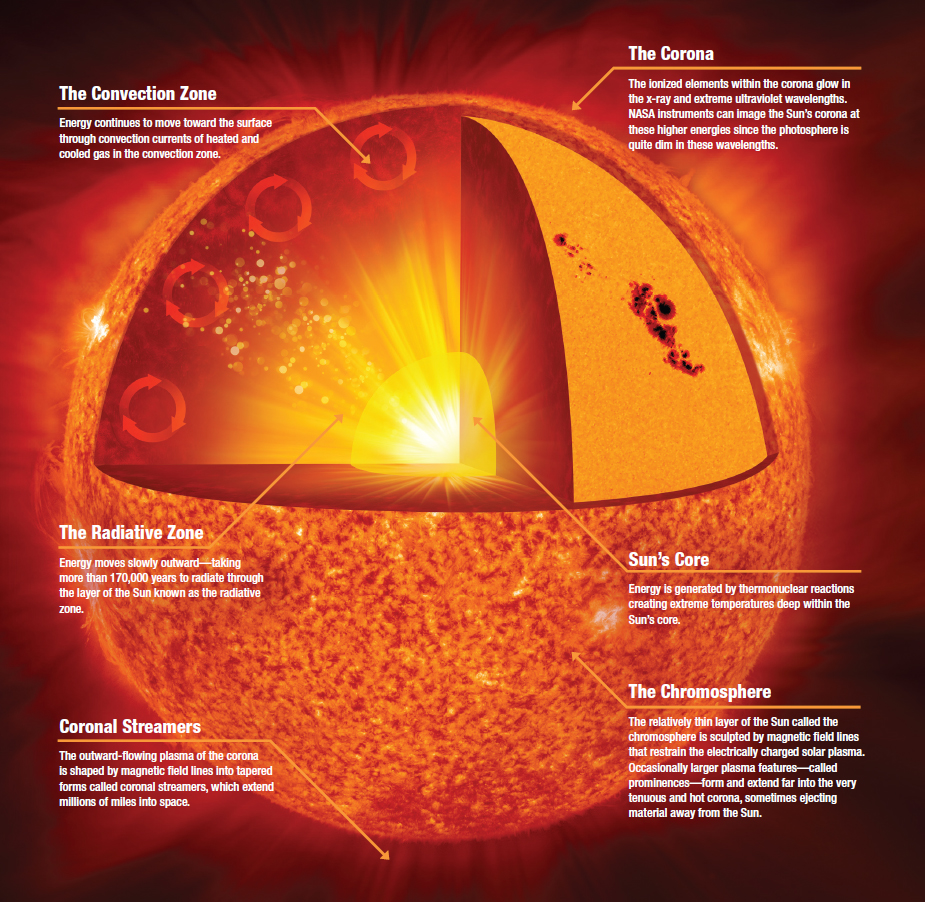

4.5 billion years ago, the Sun entered its main-sequence star phase, meaning it started fusing hydrogen atoms in its core, turning mass into energy. Four atoms of hydrogen fuse together in a nuclear reaction, to form one atom of helium. The core makes less than 1% of the total volume of our star, but contains more than 30% of its total mass. It takes the Sun 10 billion years to fuse the hydrogen fuel in the core, therefore remaining in a main-sequence star phase. As such, the Sun remains a stable star, with no significant temperature, luminosity and radius variations, at least on a cosmic scale. But what might not be noteworthy for the Universe, is momentous for life on our planet.

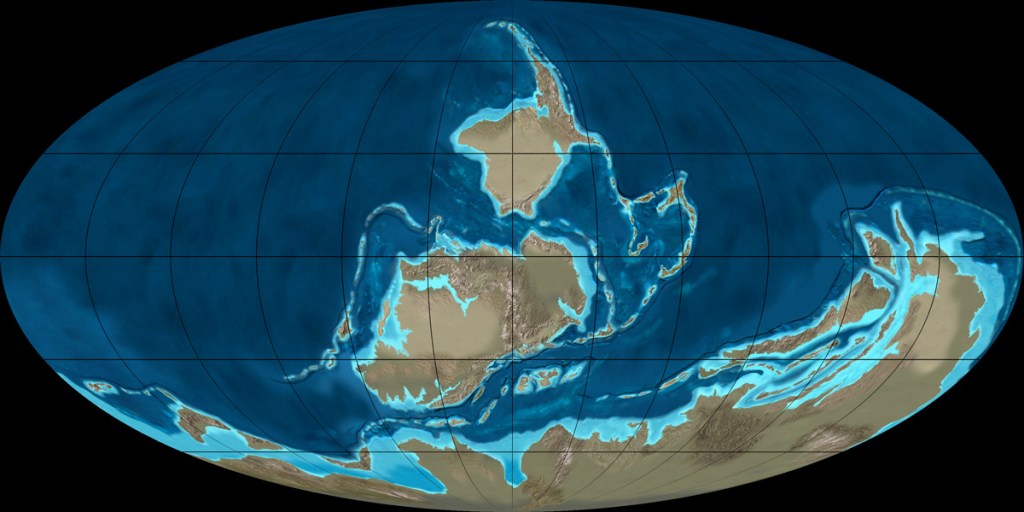

During the Ordovician (485.4 – 443.8 million years ago) the Sun’s luminosity was 95.5% of current levels. Global mean average temperature is debatable, but at the equator sea surface temperature was about 45° C (compared to current 30° C), and air temperature at the equator was 48.8° C (compared to current 22-27° C). The planet was very warm and sea levels were the highest in all Paleozoic era, at 180 m above present day.

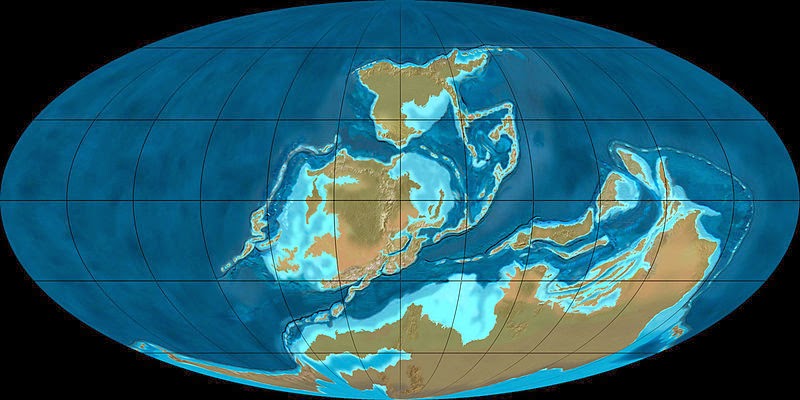

During the Silurian (443.8– 419.2 million years ago) the Sun’s luminosity was 96% of current levels. Global temperatures dropped significantly compared to the Ordovician, averaging at around 26 to 32° C, but continuously dropping towards the end of the Geological Period to below 22° C. For comparison, NASA has calculated the global average temperature for 2022 at 14.76° C.

The Devonian (419.2 ± 3.2 – 358.9) saw a further, not so dramatic, decrease of global temperatures. The Geological Period started at around 21.3° C, and ended at around 20.8° C. The Sun’s luminosity was 96.5% of current levels.

What happened? Why is the Sun’s luminosity level higher today than 450 million years ago, but the planet is significantly cooler? The temperature levels of the Ordovician were so high, it would be impossible for humans and most surface present day life to survive. The way life on Earth is shaped today, it would take one year of Ordovician temperatures to enact an extinction event comparable or even more severe than the Permian-Triassic Extinction (252 million years ago), The Great Dying, that wiped more than 90% of all life on our Planet. (-> Read more about The Great Dying here: https://astropeeps.com/2022/09/27/the-great-dying/)

The answer is: CO2.

During the Ordovician, CO2 was 4500 ppm (parts per million) to 6000 ppm. (As you might have noticed in the above paragraph, as far as Ordovician-related data go, there are only estimates, due to limited data that can be recovered from geological strata for this specific timeframe.) The Silurian averaged at 4500 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere, while the Devonian levels dropped to 2200 ppm CO2.

2200 ppm CO2 during the Devonian: more than four times higher than today’s levels of 420 ppm CO2.

You might have noticed by now, there is a strict correlation of temperature drops and CO2 levels decrease. The Silurian had lower CO2 levels than the Ordovician and therefore lower global temperatures. This goes on and on with the amount of this greenhouse gas directly affecting the mean average on Earth. However, it is estimated that in about 600 million years, our atmosphere will become completely depleted of C02, without any further natural factors capable of producing it. As a result, photosynthesis will start failing, and with it, life on Earth. By this time the Sun’s luminosity would have increased by 12%. Unlike our prehistoric past, a lack of atmospheric CO2 will no longer compensate the heightened luminosity. The average temperature on Earth will eventually reach the runaway greenhouse borderline of 47° C, a point of no return for our Planet to gradually turn into its neighboring infernal twin, Venus.

But let’s step back an entire eon from our Planet’s scorching future, to a time when complex life was still pioneering Earth and conquering new territories; to a time when life embarked on a chemical sublimation of the atmosphere, by perpetually decreasing CO2 levels, as fuel in its conquest of all land, oceans and sky.

*

Life on land

The Ordovician, the Silurian and the Devonian sum up to 130 million years of prehistoric Earth. There cannot be any linearity to such an extended period of time. Volcanism, cosmic impactors, radiation burst from supernovas and geological activity have perpetually affected global temperatures and chemical balance in both the ocean and atmosphere. The above temperature related data is only a broad picture of a specific geological period, though there were severe changes in all three of them. Small to longer periods of glaciations have triggered the increase or decrease of both sea levels and mean temperatures, prompting chemical variations of soluble oxygen and increased levels of free hydrogen sulfide in the water. Life was put through the wringer.

*

The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

Atmospheric CO2 levels during Cambrian (538.8 – 485.4 million years ago) and Ordovician (485.4 – 443.8 million years ago) were at the highest in the entire Paleozoic Era, as there was nothing to filter the air and trap the gas in the ground. The oceans would then contribute to the release of even more of the greenhouse gas, ensuing the bond between soluble oxygen with the carbon resulted from decaying algae and animals. Consequently, the planet was very warm and humid. At the beginning of the Ordovician, O2 levels in the atmosphere were merely 10%. Then came the first terrestrial plants. Though they were nothing alike their modern vascular counterparts, these moss-like plants hinged on rocks, slowly decomposing them and releasing phosphorus into the oceans. For algae it was a feast, for the rest of ecosystem it spelled mayhem, as algal blooms were shortly followed by bacterial decay that used soluble oxygen. The depletion of soluble oxygen affected the natural formation of CO2 and its release into the atmosphere. Back on land, moss-like plants, though primitive were photosynthesizing CO2 and water, turning them into glucose (C6H12O6) and releasing some of the oxygen back into the atmosphere.

By the end of the Ordovician, global O2 levels had already risen to 13%.

A possible gamma ray burst from a supernova and a definite increase of volcanic activity were also key players for the ongoing Late Ordovician Mass Extinction. Some of the ozone layer was stripped off during the gamma ray burst of a supernova; as such atmospheric nitrogen dioxide levels increased. Volcanos produced gas clouds that blocked the sun for millennia. Like knights of a climate apocalypse, the very first land plants, volcanos and a dying star pushed Earth from suffocating heat to extreme glaciation.

(-> Read more about The Ordovician Extinction here: https://astropeeps.com/2023/05/21/ordovician-extinction-or-how-the-first-terrestrial-plants-almost-killed-all-life-on-earth/)

*

The Silurian Intermezzo

A grim start for the Silurian. The CO2 levels decrease during the Ordovician were indeed notable, though not radical. Soon after the ozone layer recovered and the skies cleared from the volcanic ashes and toxic clouds, temperatures started rising again and the polar cap in the south gradually melted. Earth entered a new greenhouse phase.

The moss-like plants of the Ordovician originated in freshwater, not the oceans, and chronologically propagated into the Silurian in the genus Cooksonia, as a tiny green layer covering rocks. These plants were leafless and non-vascular, formed by stems bearing spores. In fact, this particular colonization is unique in our Planet’s history, but took tens of millions of years to develop into the type of plants we can truly relate to. And after around 20 million years, already close to the end of the Silurian, the first plants bearing leaves, such as the Baragwanathia, appeared. They were still stem like plants, reproducing through spores, but were of a brand new genus, the lycopsids, with thicker surfaces shielded by vertically arranged leaves and wider grip to the ground, allowing them more freedom to grow vertically.

As plate tectonics continued shifting, several islands near the equator were swallowed by the ocean, while Laurentia and Baltica came closer together, narrowing the Paleo-Thetis Ocean. Gondwana first shifted towards the south, then back towards the North Pole, expanding the shallow seas that could blossom with new life. Bony fish appear for the very first time. Tentaculoids are spreading and diversifying. The clade of sharks, most probably already present during the Ordovician is growing. Trilobites, severely affected by The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction, recover and flourish, but will never regain their past reign in numbers and diversification. All in all, we can affirm a true heyday for life in the oceans during most of the Silurian. There were at least 15 major climate changes during the almost 24 million years of this geological period, each acting as a very small extinction pulse, though nothing to radically affect life. And on the very peak of the food chain, undebatable king stood the sea scorpion, of the group of Eurypterids, a fearsome predator with large pincers that could reach 2.5 m in length, making it the largest animal on Earth during the Silurian. Fish had developed jaws and teeth and had become more efficient in providing food for themselves, but were still very small and would have had no chance in dethroning the large sea scorpion that did have one major shortcoming when it came to hunting the ever more evolved and efficient fish: it was a terrible swimmer, a trait that would push it towards its downfall during the Devonian.

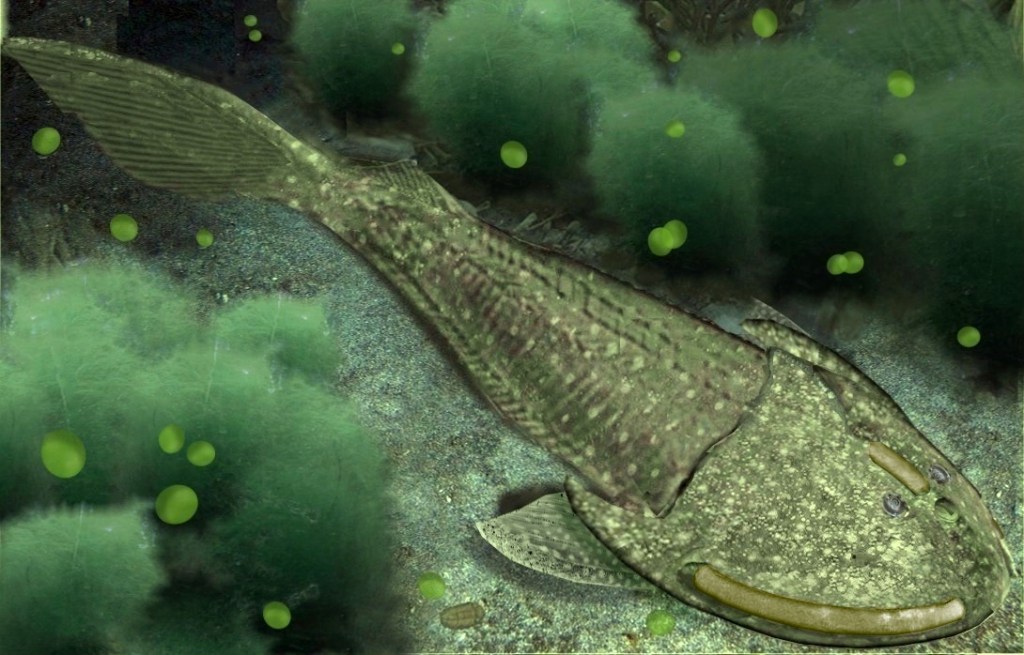

Photo copyright: Lucas Lima and Earth Archives

But something amazing happened on land!

Except for bacteria and plants, life on dry land had no precedent in our Planet’s entire history.

During early Silurian a group of aquatic myriapods ventured on land. Some crustaceans and other aquatic arthropods shortly followed. First they stayed near the shores and in swamps. As millions of year passed, they adapted to breathing air, no longer depending on soluble oxygen from the water. And while these first land creatures were turning into the first millipedes, insects and arachnids, completely independent from bodies of water, so did plants adapt into coexisting with them.

Water was no longer the only animated place on Earth. The air had started to be disturbed by the sound of fauna, by the sound of life.

*

The Devonian Revolution

Writing about the Late Devonian Mass Extinction was a real challenge. Out of all five mass extinction events, the Devonian is the least severe, eliminating only 70% of all species, predominantly in the tropical and equatorial areas of the Planet. It is also the most ambiguous extinction event of all five. There is no clear culprit, and there are at least ten minor extinction pulses that have contributed to it. Not much detail has been dedicated to this particular extinction event, and it has always been widely overlooked, compared to, let’s say, The Great Dying (The Permian-Triassic Extinction Event, 252 million years ago, -> https://astropeeps.com/2022/09/27/the-great-dying/), that has pushed life on Earth to the brink of total and permanent collapse. We know about the intense geological activity during the Devonian, we also suspect several cosmic impactors, but there is nothing as earth-shattering, literally, to point towards an episode that could be enclosed inside a clear definition of a major extinction pulse. Therefore, I decided to retrace the evolution of life linked to climate, chemical balances in the oceans and atmosphere, geological activity, not only during the Devonian, but starting with Late Ordovician, when plants began adapting to dry land.

There is no Late Devonian Mass Extinction! At least not in a way we could point it out inside a specific geological timeframe. The Late Ordovician Extinction had, in fact, never ended, but continued throughout the entire Silurian and Devonian, as the insidious battle of life, fighting to redefine its surroundings, so that it could turn it from a geological system, into an ecosystem.

The Revolution of Terrestrial Plants

Tectonic activity was intense during the entire Devonian. Gondwana, comprised of Antarctica, Australia, parts of Southern Europe, the southern part of the African continent, India and Arabia, remained in the Southern Hemisphere, surrounded to the north and north-east by island arcs and large land masses. The Devonian saw a constant friction of tectonic plates between this giant continent and the surrounding areas, pushing towards aggressive collisions that triggered volcanic activity and igneous intrusions, called plutons for the Devonian, as the size and characteristics cannot be well defined during this Paleozoic phase. These igneous intrusions are defined by the very slow cooling and crystallization of magma below the surface forming igneous rock, or magmatic rock. One outcome is the creation of island arcs. Another is the entrapment of large quantities of CO2 into the mantle. The upward magmatic intrusion into the oceans will also raise the water temperature, depleting it from some of the soluble oxygen.

The other large continent, Laurentia, comprised of most of Europe and North America, drew closer towards Gondwana, compressing the Paleo-Thetis Ocean further, compared to the Silurian. The collision of the two land masses forming Laurentia: Baltica (comprised of North-Eastern and Western Europe) and North America, prompted the rise of several mountain ranges, such as the Appalachians and the Caledonians. Laurentia shifted towards north-east, pushing the small continent to its north (what would be today’s Siberia) even farther into the Northern Hemisphere, but also capping the Paleo-Thetis Ocean between Gondwana and Laurentia.

All of this tectonic activity resulted into even more areas of shallow seas, a very warm and humid global climate and not so radical differences in temperatures between the equator and the poles.

Plants have had some tens of millions of years by now to stabilize some of the soil near bodies of water, but were not quite holding a grip as to allow them to grow vertically at notable heights.

This is a time for true conquest of the land, though in rather peculiar ways and shapes, not resembling anything we could identify in nature today.

The preexistent Cooksonia plants diversified during Early Devonian, with branches containing spores. These plants also adapted to larger more elongated cells, that could preserve water more efficiently, and a wax covering that would protect them from desiccating. As they started to widen their root area, so did they begin to struggle for more light, developing tiny leaves on their branches.

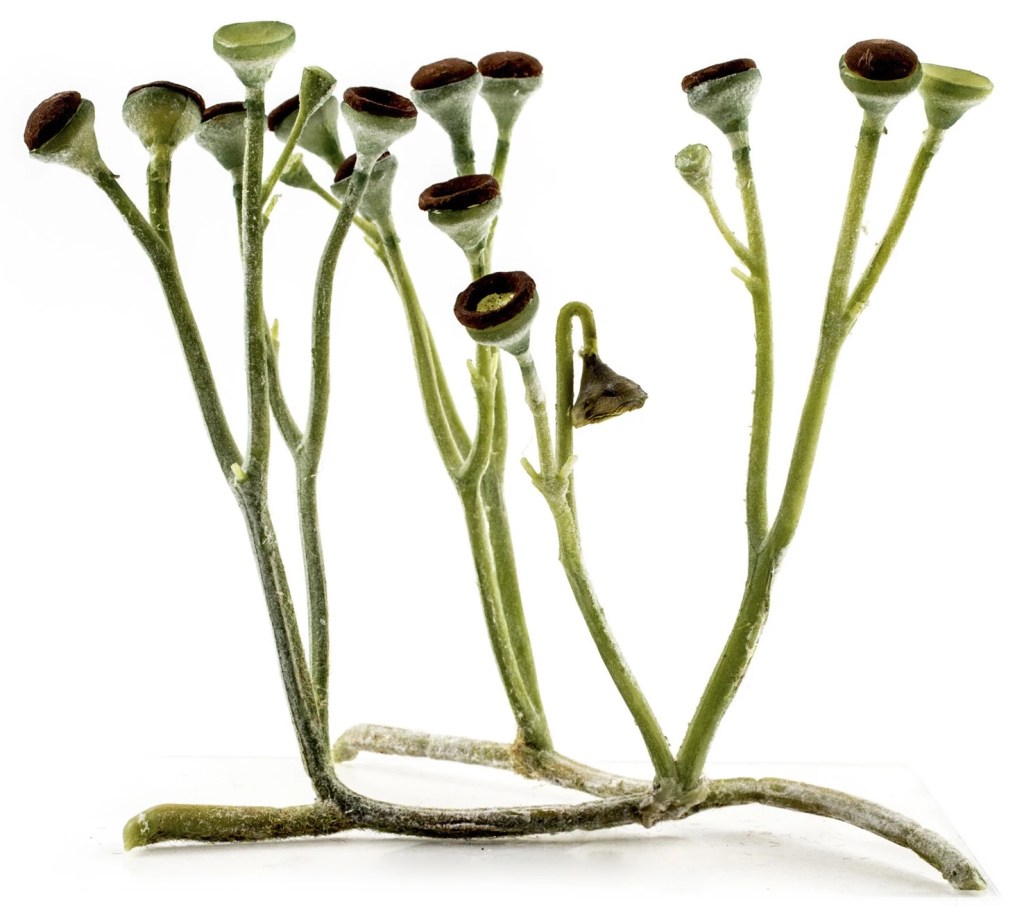

There were already several other genera of plants that had started to diversify during Late Silurian. The previous stalk-like plants expanded their volume and height, but still depended on a very primitive life cycle of growing, producing spores and dying. One Example is the Sciadophyton, emerged during Early Devonian, that produced a ray of stems bearing umbrella-like spore cups, with both male and female sex cells. The plant heavily depended on rain to fertilize the female spores, create sporophytes and propagate.

Much of the Devonian landscape, however, has been defined by the very strange Prototaxites. These land fungi first developed during Late Silurian, but conquered towering heights in the Early Devonian. When we envision an Early Devonian surrounding, we need to understand that everything was small and close to the ground, at least until Late Devonian. Almost everything, as Prototaxites would dominate the entire landscape for many millions of years! These fungi were gigantic, reaching 8 m above the ground, with a depth of 1 m in cross-section. It has been long debated if these organisms were indeed plants or fungi, but considering their imposing heights and the unadapted terrain for deep roots, their woody masses couldn’t have sustained them, therefore it is almost certain they were giant fungi, but with no explanation to date as in why and how they reached such imposing statures and wide range dispersion. They did however have an important role in nourishing and softening the soil, trapping nitrogen from the atmosphere and decomposing pioneering carbon rich plants. One of these was the Asteroxylon, that unlike its primitive Silurian relative, the Baragwanathia, had developed branches covered in vertical leaves. By Mid-Devonian the first tree-like plants appeared. The Eospermatopteris, the very first tree to appear on Earth, could reach 8 m in height, but would still reproduce using spores. By approximately the same time, the Calamophyton appeared. Shorter in size than the Eospermatopteris, both these trees would shed their leaves continuously, providing early arthropods a nourishing ecosystem.

The Prototaxites slowly retreated by the Late Devonian, and were replaced by a new range of plants, that would revolutionize the land. The Archeopteris was the first true wooden tree, and unlike all its predecessors, would no longer shed its leaves continuously, but could bare them for extended periods of time. It would still reproduce using spores, but these were encapsulated into cone-shaped structures, allowing them to spread quickly and more efficient, therefore growing the very first forests on Earth.

And as the Devonian was coming to an end, so did the first plant-bearing seeds appear. The Elkinsia, though leafless, and primitive, could rise 1 m above the ground, but would encapsulate seeds, not spores. This extraordinary evolution was momentous for plant life on Earth. Unlike spores, seeds contain nutrients and an embryo of the future plant, making them so much more proficient and resilient.

Photo copyright: Richard Jones/Science Source

Plants had their foothold on land, and just like the Late Ordovician, had caused the same chemical stir in oceans and lakes, with the exact same patterns. Rocks were decomposed, phosphorus enriched the oceans and lakes, algae thrived, bloomed, died, were decomposed by bacteria that would deplete the water from soluble oxygen.

Photosynthesis, algal blooms, Laurentia and Gondwana moving closer together, volcanic activity and plutons: all wreaked havoc in the oceans. Life on land was struggling to evolve, while life in the seas was struggling to survive. And some of it found an unexpected alternative, that would start a journey of several hundreds of millions of years, leading straight to us.

*

The Revolution of Life

From start to finish, the Devonian saw an initial increase of atmospheric oxygen levels to around 19% by the Mid-Devonian, to a decrease of 17% by Late Devonian, to a very rapid increase to 33%-35% towards Mid-Carboniferous, some 330 million years ago. Overall oxygen levels were much higher compared to the Silurian (443.8– 419.2 million years ago). Yet during the 60 million years of the Devonian (419.2 ± 3.2 – 358.9 million years ago), though plants directly contributed to the rise of oxygen, various dramatic events, such as volcanism and cosmic impactors have meddled negatively, pausing the process. And as we saw earlier, the increase of atmospheric oxygen, also led to the decrease of soluble oxygen in the oceans. Negative variations of oxygen levels in the atmosphere then led to temporary increases of CO2, prompting longer periods of global warming and the melting of the southern polar cap almost completely.

The Devonian is widely known as the age of fish. Aquatic life during Early- and Mid-Devonian was overall abundant and variated, in both fresh- and saltwater. Sponges, brachiopods, arthropods, including trilobites and cephalopods were thriving in the relatively calm shallow waters surrounding the two supercontinents and their satellite islandic rows and protocontinents. The Eurypterids, including the giant sea-scorpion, diversified further and started their attempt to leave the water and try breathing air on dry land. They were still ferocious predators, but didn’t develop better techniques of swimming, thus remaining bottom feeders. Their group will be severely affected during the Late Devonian, with the giant sea scorpion going extinct. Only the smaller members of the group managed to survive, the most successful being the ones that managed to adapt to breathing both underwater and on land.

Osteostracans were some of the most successful and wide-spread jawless fish, shielded by a bony horseshoe-head. They appeared in various forms and large numbers, but they were also bottom feeders. When the oceans became anoxic during Late Devonian, the entire group went extinct.

Sharks also continued their successful evolution in both diversity and efficiency, but continued staying under the radar as major predators. One example worth mentioning is the Stethacanthus, with its very distinctive “ironing board”-shaped upper fin, that males used for gripping female sharks. Being more versatile and adaptable to their surroundings, sharks managed to overcome the harsh anoxic changes in the oceans. They were also affected, but could adapt better to new environments, including deep ocean, and were better swimmers, therefore, sharks successfully stepped into the Carboniferous.

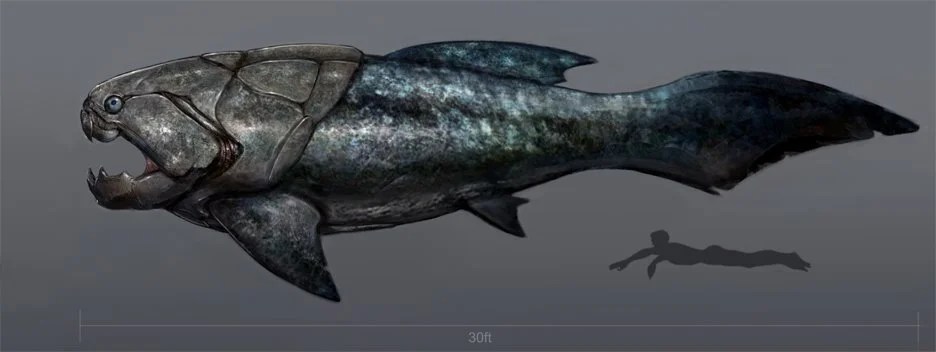

But the most impressive fish of the Devonian were the placoderms. The head and thorax of these fish was covered in articulated and armored plates, while the rest of their bodies usually lacked scales and was unprotected. These fish first appeared in the Silurian, but during the Late Devonian, one of them became the apex predator and also the largest animal on the Planet: The Dunkleosteus. Unlike other placoderms, this one was a killing machine. The armored plates did not cover its pectoral fins, therefore not hindering its swimming and mobility speed in any way. Its jaws were enforced by articulate head plates, that would erode as the fish grew older, turning into fangs that would make the Dunkleosteus even more efficient. Reaching 6 m in length, the Dunkleosteus was a very territorial animal. In fact, almost every fossil to have ever been discovered is severely scarred, meaning it was fighting for territorial primacy with other members of its clade. It did however have one major shortcoming, as did all placoderms: they were only adapted to shallow seas. Unfortunately, this was the vulnerable spot that hindered the entire group from ever stepping into the Carboniferous. On the other hand, one exceptional characteristic of placoderms was the evolution of internal fertilization. The Materpiscis is believed to be the first animal were the embryo is tied to its mother via umbilical cord. For the first time in Earth’s history, eggs were no longer fertilized outside the body, but inside, giving the embryos better chances of survival. Relatively soon after, other animals would start developing this particular feature as well.

Sadly, the placoderms, including the Dunkleosteus, went extinct as soon as the Devonian came to an end. The downfall took up to a million years, but while other species managed to adapt to ever more anoxic oceans, the placoderms, though undefeated predators, died out, as their lungs could no longer adjust to new conditions, and the group of fish could not acclimate to the deep ocean were soluble oxygen levels were higher.

*

Today we find an abundance of life even in the deepest parts of the ocean, but 358 million years ago, complex life was still in its prime, and could not adapt so easily to new conditions. When Mid-Devonian was coming to an end, anoxic waters started to become common place, spreading all over the shallow seas. The climate became warmer and as life in the ocean was withering, life on land was flourishing.

A small group of fish, The Eusthenopteron, meaning “good strong fin”, found an alternative to survive. Rather than turning to the deeper parts of the ocean, less affected by oxygen depletion, The Eusthenopteron turned towards the shores. Their lungs evolved, and their snout elongated, their fins developed bony limbs comprised of seven digits each. They crawled their way out of the water, but never too far away from shores, wetlands, marshes and swamps. By now, arthropods were already well established on land. The Tiktaalik is believed to be the first tetrapod to leave the seas and adapt to breathing air. Though it never fully abandoned the shallow waters, it could also successfully survive on the ground, feeding on insects, millipedes and small arachnids. The Ichthyostega, the first tetrapod to have been discovered, though younger than the later discovered Tiktaalik, features some impressive traits that proves its successful journey from the waters on dry land. Its thoracic chest is fully developed and closed, meaning its lungs were no longer pressed upon by other organs, when leaning on the ground, but protected by ribs united by a sternum. The shoulders and limbs have strong muscles that suggest the animal used them to crawl out of the water.

Vertebrates were no longer restrained to living under the surface of oceans and lakes, but had begun their successful history as rulers of the land.

*

With the Carboniferous (358.9 – 298.9 million years ago), the world looked radically different than it did at the beginning of the Devonian. Barren lands had become green even in the most remote places on Earth; rock turned to fertile soil covered in forests; the land was teeming with life, and on the shores, you could see the very first footsteps of the very first tetrapods, our very first ancestors on land. The Planet was now alive, everywhere, for millions of years to come, to evolve, to diversify, to stay resilient against all adversities, to stay animated against the perils and darkness of the Universe.

– Roman Alexander

Leave a reply to Two Million Years of Rain – The Carnian Pluvial Episode – ASTROPEEPS.COM Cancel reply