Due to current climate changes triggered by overconsumption, high CO2 emissions, ever growing plastic waste, wars and nuclear threats, humanity is galloping towards the brink of extinction.

Read that last part again!

It is not life on Earth that is on the brink of extinction, it’s humanity.

As of September 26, 2022, current CO2 levels in the atmosphere are around 420 ppm (parts per million), higher than they’ve ever been in recorded history. (In comparison, preindustrial levels were around 280 ppm.) Rising CO2 levels trigger a chain reaction by letting visible light pass through the air, yet absorbing long wavelength infrared energy, preventing the planet to cool itself down. With a global temperature increase, permafrost – trapping more than 1.5 trillion metric tons of carbon – near and towards the Polar Circle, in the Northern Hemisphere, will start disintegrating, releasing more CO2 than humanity could ever be capable in producing by burning fossil fuel. Worst-case scenario, a global increase by 4°C by 2100, agricultural failure, dramatic migrations towards the poles, devastating and perpetual forest fires and rising sea levels. Without immediate response, we will not survive this man-made extinction. And news flash! There is no immediate response, no global plan agreed and practiced upon to reduce CO2 emissions. Never-ending conferences and highly mediatized promises about climate change do not stand for a planetary band aid.

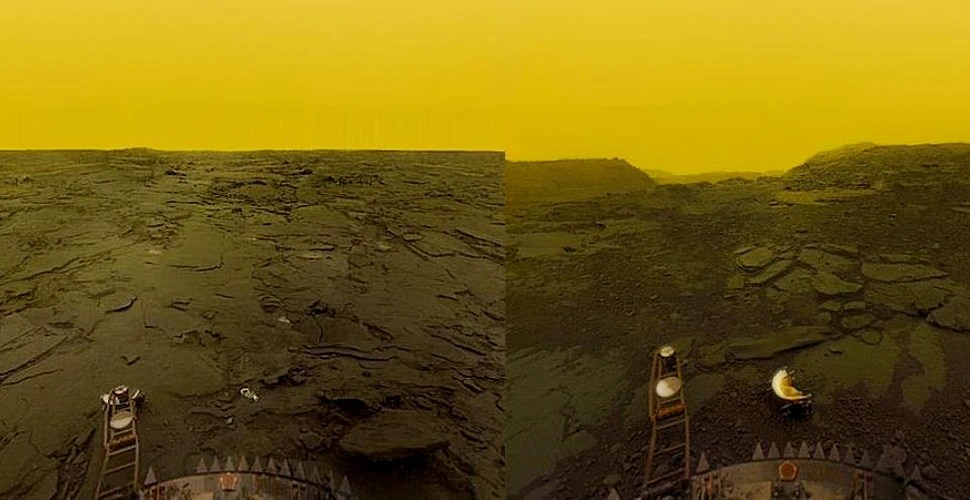

But if our species disappears, so will life on Earth? Considering the whole bundle of worst-case scenarios, has there ever been an event more destructive for life on Earth, then the one we are currently perpetrating? There has! More than once. Though one in particular experienced CO2 levels 20 times the ones currently present in our atmosphere. As a matter of fact, this series of concurrent extinction pulses, colloquially known as “The Great Dying” almost pushed Earth towards a runaway greenhouse effect, to the brink of turning it into the scorching inferno of our twin-planet Venus.

Rise and Fall of Oxygen

Long before The Great Dying, about 359 million years ago, Earth entered its Carboniferous geological Period, fifth age of the Paleozoic Era.

If, during Devonian (419.2 to 359.2/358.9 million years ago), Earth’s atmosphere consisted in oxygen levels no more than 18%, The Carboniferous (359.2/358.9 to 299 million years ago) saw an increase to 25% by 350 million years ago; 30%, 50 million years later, to more than 35%, for a brief period in the following million years. Might sound tempting to us humans, yet oxygen is a toxic gas, if above the levels we are accustomed to (21%). So don’t dream about the lush forests and humid everglades of the Carboniferous, as, contrary to popular believe, we would be able to think more rapidly and clearly, though not for long. Our lungs, too large for such amounts of oxygen, would eventually collapse, while we would gradually pass through a state of euphoria, nausea, muscular spasms, vertigo and death.

And yet, life did thrive in these conditions. It diversified in both sea and on land, though the greatest beneficiaries of the large oxygen levels were insects that reached colossal sizes, compared to what we are accustomed to, thus defining the Carboniferous as the Age of Insects. True, they were large in size, but still far outnumbered by contemporary levels, where the human to insect ratio is 1 to 300 million. I guess we should reconsider if we are truly living in the age of humans or the age of insects.

Rewind to the Carboniferous, there were still no saprotrophs on land, as in plant decomposing bacteria. Today, saprotrophs are all over the planet, decaying dead plants and releasing CO2 back into the atmosphere. Back then, no saprotrophs meant, no CO2 resulted from decaying plants, therefore leading to stacking amounts of coal deposits over a period of more than 60 million years, consequently naming the fifth age of the Paleozoic Era: the Carboniferous.

In an environment of ever-growing amounts of oxygen, a humid and somewhat warm global climate, arthropods such as the Meganeura Monyi, similar to today’s dragonfly, had a wingspan of 75cm. The giant millipede Arthropleura Armata reached a length of 2.5m and a width of 50cm, though besides its colossal size, it fed only on plants, and not on today’s people’s nightmares. Giant scorpions reaching up to 78cm in length (Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis), flying half-a-meter insects (Mazothairos enormis), cockroaches four to five times the size of modern ones thrived in this environment and evolved, largely with the help of high oxygen levels, in order to avoid their land predators, consisting mostly in amphibians and reptiles.

In fact, the Carboniferous sees the rise of tetrapods, as in amphibians, reptiles, sauropsids and – during the Late Carboniferous – the synapsids, the very first mammal-like creatures to have walked the face of our planet.

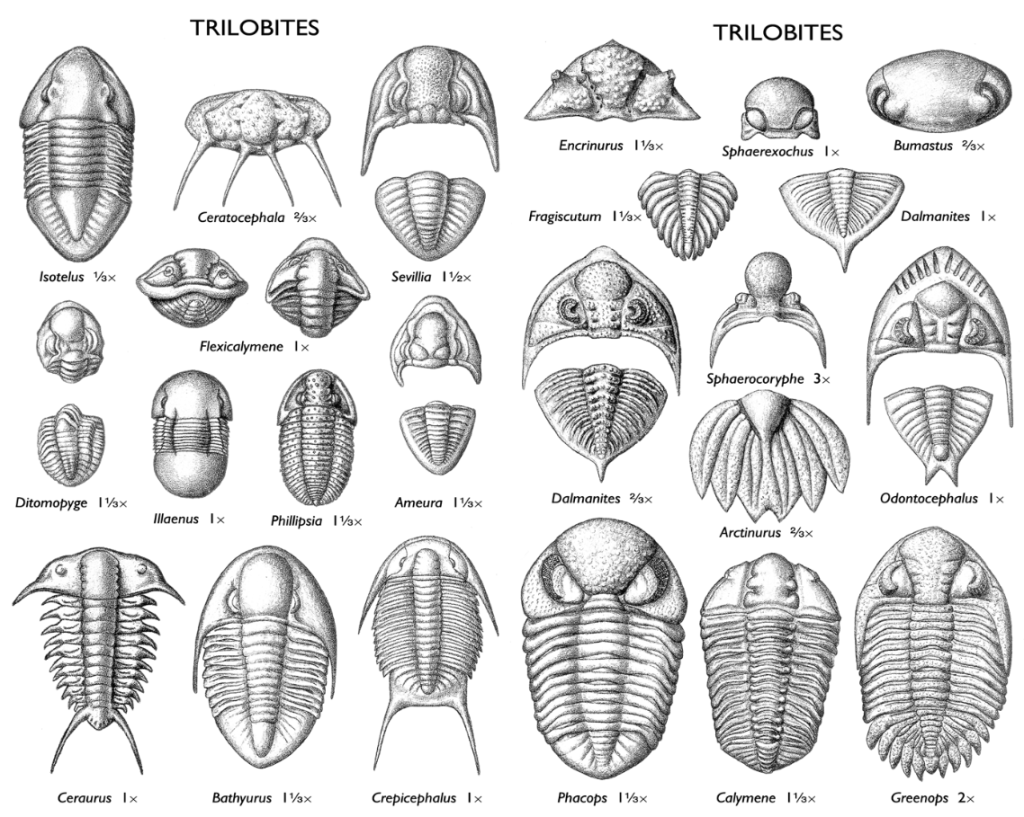

Fish started diversifying in water, though the dominant groups in our oceans were still invertebrate marine creatures such as: corals, bryozoa, brachiopods, ammonoids, and echinoderms (mostly crinoids). The exceptionally resilient trilobites, who had been inhabiting the oceans by now for about 200 million years, were still around, but their class was already heading towards a very slow extinction, that will sign its final chapter during The Great Dying.

All in all, life on our planet was still very dependent on water, as even land creatures were predominantly living near seashores, riverbeds and swamps.

Carboniferous collapse. Rise of the Permian.

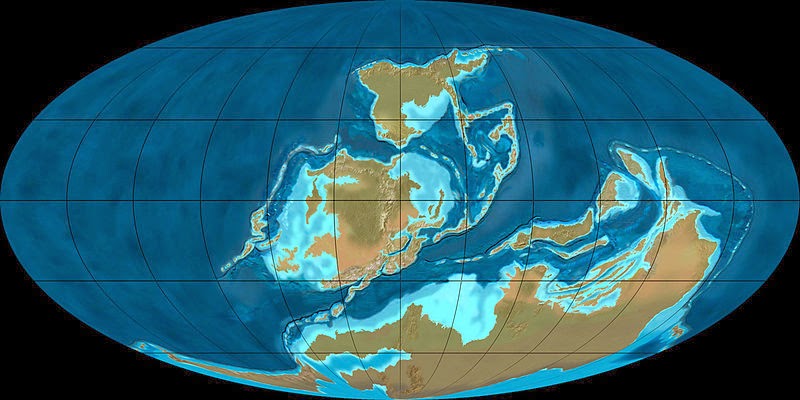

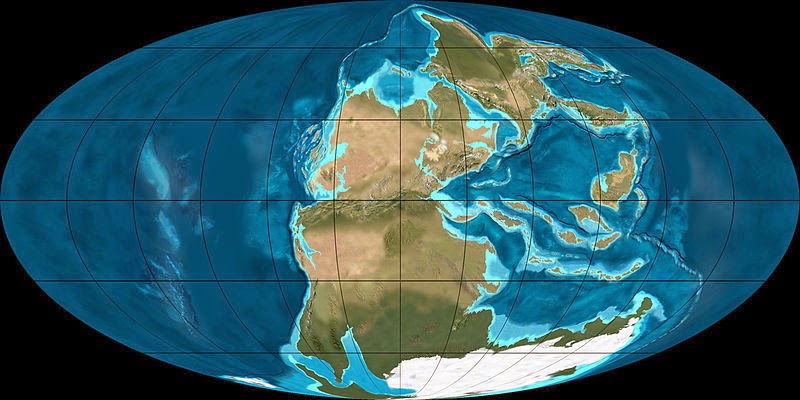

There is a downside to not having saprotroph bacteria to turn dead biomass into CO2. The continuous release of oxygen, triggered by the expansion of ferns, scrambling plants, mosses and scale trees all over land during the Carboniferous, depleted the atmosphere of carbon dioxide, leading to a global cooldown from 20°C to 12°C by 305 million years ago. Furthermore, the two continental blocks, Gondwana and, the smaller, Laurasia, finally collided into a supercontinent: Pangea, that would last for about 100 million years (till approximately 200 million years ago), when they would eventually rift into the modern continents, we all know.

A planetary drop in temperatures, loss in oceanic streams due to the huge, ever more compact land mass of Pangea, perpetrated the collapse of the Carboniferous rainforests, starting a chain reaction with a major drop in global oxygen levels, triggering the extinction of large subgroups of reptiles and amphibians, shallow water fish, almost all giant arthropods and several species of giant insects, that relied on warm and humid climate and high levels of oxygen.

Enter Permian (299 to 251.9 million years ago), last geological Period of the Paleozoic Era.

Unlike its predecessor, the Carboniferous, The Permian, spanning over a period of 47 million years, is widely considered the starting point towards the diversification of large land creatures, that can survive harsh conditions, and rely as little as possible on water. The merger of land into Pangea, with a surrounding Panthalassa, to cover the rest of the planet, meant a decrease in precipitation towards the inland super continent, turning a once lush marshland and forest into a giant desert. Amphibians, relying on shallow waters to lay their eggs, saw a major decline, as the amniotes replaced their ancestors as dominant land creatures.

As far as the amniotes are concerned, they started evolving from amphibians during the Carboniferous, yet it is the Permian that sees this clade of tetrapod vertebrates gain territory, numbers and diversification inside an ever-drier continental Pangea. The two dominant clades: synapsids (with a single temporal opening) and sauropsids (with two temporal openings), set their footprint as ancestors for most land animals that will continue their evolution throughout the rest of Earth’s geological eras, until present day.

Sauropsids (predecessors of reptiles, including dinosaurs, and birds), evolved into laying hard, calcified shelled-eggs, that no longer required water, in addition to protect the embryo. These animals will eventually dominate the Mesozoic era (252 to 66 million years ago), due to their higher survival rate – compared to the synapsids – during the Great Dying.

Synapsids, ancestors of mammals, were initially mammal-like reptiles, that dominated the early Permian, diversifying at a rapid pace, including several apex predators like the dimetrodon and the edaphosaurus, both reptile-looking, with a large boney sail on their backs. These early synapsids did not tolerate the rapid climatic and geological changes leading to the Mid-Permian, and by the end of this period, they would have already been replaced by a new and improved clade, the therapsids. These animals were more familiar looking to what we know of today, some of them being covered in fur, others in glandular skin, and others in a mixture of scales and fur. Among them, the gorgonopsids (evolved by 275 million years ago) became the largest land predator, with an elongated skull, proeminent, sharp, upper canines and an increased sense of smell.

And along with the gorgonopsids came the cynodonts, also successors of earlier synapsids (pelycosaurs). These predators hunted mostly in packs, and much like the gorgonopsids, had canine-like teeth. Cynodonts were also the clade with the best survival rate during the Great Dying, as they were smaller and their bodies were closer to the ground, allowing them to hide and protect themselves more efficiently. Gorgonopsids, on the other hand, did not survive the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event.

There is no fossilized record of eggs for any of the synapsids. The most plausible reason is that they may have laid leathery eggs, lacking the calcified shell we encounter in reptiles, and they most certainly developed mammary glandes, as the last synapsids to appear before the Great Dying, the cynodonts, are the ancestors of all mammals we know of today.

On a vast land, no longer defined by a homogenous humid climate, plants started diversifying. The fern-like- and mossy plants, predominant during the Carboniferous, adapted to harsher climate and territory. Some developed a vascular internal system to transport water, others, like the protoangiosperms (ancestors of flowering plants) adapted to coexist with insects and their unprecedented ability to pollinate. By the second half of the Permian, gymnosperms, ancestors of conifers, also came into existence, as their seeds were more resilient and easier to spread in drier lands.

With the increase in global temperatures, marine life became more abundant and diverse than it is today. As trilobites continued their descent into permanent extinction, boney fish, such as sharks and rays thrived. Brachiopods, ammonites, coral reefs and sponges conquered the seabed of the giant Panthalassa, enveloping more than 70% of our planet’s surface.

All in all, life on Earth was thriving, diversifying and evolving as never before.

And then… everything plummeted into a downward spiral of doom, that lasted for more than 150.000 years, almost turning Earth into our twin planet Venus, with a runaway greenhouse effect that could have changed our home into a scorching, dead inferno.

The Great Mass Extinction

Despite previous theories, the Permian extinction was not triggered by an asteroid. You see, when a large asteroid (such as the one that killed the dinosaurs, 66 million years ago) hits the Earth, it briefly spikes global temperatures, only to be followed by a very long nuclear winter. In the aftermath of such a collision, Earth’s atmosphere is engulfed in a thick layer of vaporized carbonate rock mixed with water, preventing the Sun to reach land and sea. The surface of the planet starts cooling down, devastating all light-dependent plants, tearing down the entire food chain. (Read more about the Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction Event here: https://astropeeps.com/2021/02/25/cretaceous-paleogene-extinction-the-chicxulub-event-and-the-fall-of-the-dinosaurs/)

The Siberian Traps

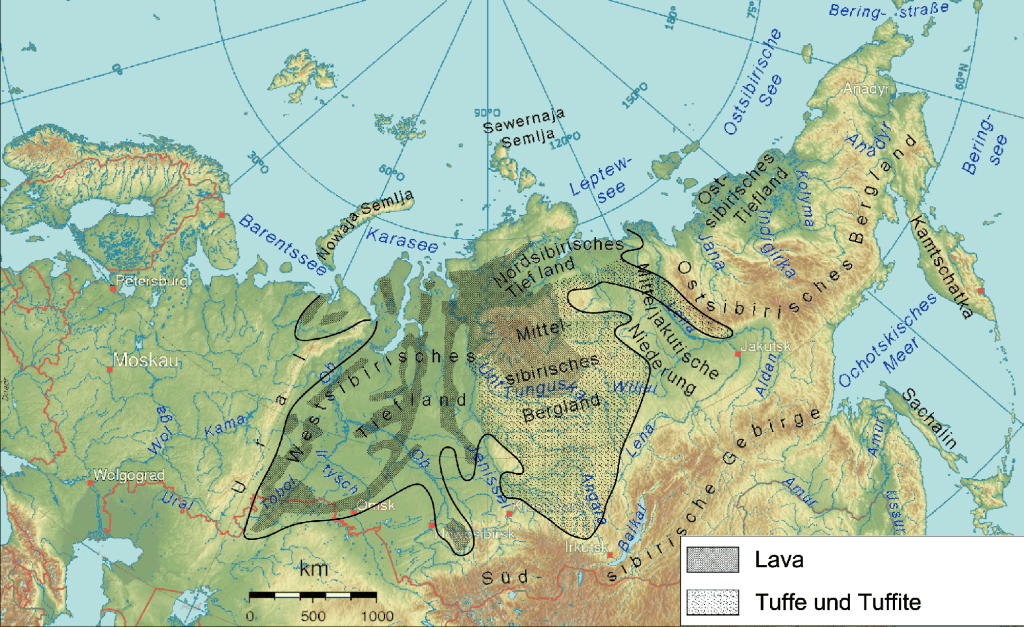

Sedimentary rock from 252 million years ago points to a rapid increase in global temperatures, of 11° C, evidence against an asteroid impact. There is also evidence of large basalt flood magma during the same period. Over the last millions of years of the Permian, massive amounts of magma started building up under the northern hemisphere of Pangea, in a territory known as the Siberian Traps. Unlike other active volcanic territories on our planet, there were not enough craters or peaks in the Siberian Traps, for magma to be gradually released. The built-up pressure beneath the surface, finally cracked the crust to a scorching flood that engulfed a region larger than the entire continent of Australia with magma. Everything inhabiting these lands and surroundings died… the result:

Global death toll: up to 20%

It has been calculated that the Siberian Traps released basalt flood magma, approximately 1 km deep, over several hundreds of thousands of years. And with magma, ashes and toxic gases were released into the atmosphere. Sulphur dioxide mixed with water, came back on earth as acid rain, burning most living plants. Herbivores and insects relying on these plants died out, as acid rain eventually enveloped the entire planet.

With the release of Sulphur dioxide, the basalt flood of the Siberian Traps also vaporized ever increasing amounts of carbon dioxide. As most plants withered and died all over Pangea due to the acidic rain caused by the Sulphur dioxide, there was nothing left to keep in check global CO2 levels, that would eventually spike to twenty times the amounts per million we see today in Earth’s atmosphere (over 8000 ppm, compared to today’s 420 ppm). Some regions of the planet witnessed a temperature spike of more than 30° C, turning life impossible anywhere else except for the regions near the poles. By this point, life on Earth was already on the verge of total collapse… the result:

Global death toll: 40 to 50%

Yet the Great Dying, isn’t just one sole event, but a series of extinction pulses, all seeming to come from our planet’s bowels, in order to raze life in its entirety.

The pink ocean

There is clear evidence, that even before the Great Dying, parts of the ocean became anoxic, as in severe loss of dissolved oxygen. During this time, carbon, nickel and uranium deposits discovered in the ocean are far larger, than what might have been caused by the Siberian Traps. And we might know exactly what triggered this event.

Preceding the eruption of the Traps, a single celled organism (an euryarchaeote archaea called Methanosarcina) began blooming in the ocean, consuming large carbon deposits and releasing methane in the water and atmosphere. As a result, the ocean became anoxic, decimating marine life anywhere these colonies of methanosarcina were thriving.

Large concentrations of CO2 in Earth’s atmosphere not only heated the land, but also the ocean, preventing oxygen even further to dissolve. And in these anoxic waters, sulfate-reducing bacteria, along with the methanosarcina, started thriving, releasing enormous amounts of hydrogen sulfides into the ocean, turning it euxinic (rich in hydrogen sulfides). As a consequence, Earth’s shallow waters turned pink, and remained so for several tens of thousands of years. Marine life was devastated, and except for algae, not much else could survive this toxic waters. More than 95% of all species in the sea were now extinct, including the oh so resilient trilobites, that had survived on the planet for much longer than any other multicellular complex organism. As methane was released from the ocean into the atmosphere, average temperatures on Earth reached 42° C… the result:

Global death toll: more than 90%

47° C! This would have been the definitive turning point for a forever barren Earth, unable to support any life forms. At 42° C, global temperatures were just 5° C short for life on our planet to cease all together, and for Earth to start galloping towards the atmospheric pressures of Venus, and its lethal 464° C surface and perpetual toxic clouds.

The Siberian Traps continued erupting for almost half a million years, but gradually slowed down, releasing less and less CO2 and Sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere.

On land, all top predators had gone extinct. Small animals managed to survive, by hiding underground and scavenging for food. Algae in the ocean, though severely affected, continued to release oxygen into the surface waters and atmosphere. But life on Earth was still on a long path towards recovery.

It took biodiversity more than 50 million years to bounce back to the levels prior to the mass extinction, with fragile marine life, such as corals and sponges being the last to reemerge.

By 230 to 200 million years ago, Pangea finally started rifting, opening the path to the Atlantic Ocean. Water was no longer stagnant inside a giant body, but began circulating, thus cooling the global climate and reversing the anoxic and euxinic effects triggered by bacteria and volcanic activity during the Great Dying.

Synapsids, in line to rule the Earth during the Permian, evolved into the first mammals, yet remained far below the top of the food chain in the following Mesozoic Era. Sauropsids, proved to be much more resilient and sturdier during the mass extinction, evolving into dinosaurs, as ruling species on Earth, up to the Chicxulub event, 66 million years ago, when life transitioned to its long history towards the evolution of humans.

So let us not forget that today, it is not the planet, nor is it life on Earth that is on the brink of extinction, it is us. Life always finds a way to move on, and it doesn’t necessarily have to bear us into future existence.

– Roman Alexander

Leave a reply to The Devonian Extinction and the (R)Evolution of Life on Land – ASTROPEEPS.COM Cancel reply