Cosmic harmony: the apparent and unusual trait of a solar system, our Solar System, in defiance to the general chaos of a violent, destructive and ever morphing universe. A main-sequence star circled by four terrestrial planets, a belt of asteroids locked in orbit by a gas giant, followed by three more gas planets, a second belt of asteroids and the far reaches of our Sun’s gravitational influence, the Oort Cloud. Except for some minor events, nothing seems to disturb the alignment as we, our forefathers and our far future descendants know, knew and will know it.

There is no need to look into the darkness of space to find traces of chaos in our own galactic backyard. They lie in plain sight, as a reminder of how aggressive the history of our solar system used to be and will turn out billions of years from now, when our beloved star will exhaust the hydrogen fuel in its core, by fusion into helium atoms, thus bloating into a red giant, towards the planetary nebula it will leave behind.

Simulation of the proto-solar-system

Around 4.5 billion years ago, a giant cloud of cold hydrogen gas collapsed to form our Sun. As our protostar passed into its main-sequence stage, the remainder of gas and other cosmic debris began clumping together to create the planets. First, there was Jupiter, a failed attempt to a second star in what might have become a binary system. We have already discovered thousands of hot jupiters, exoplanets orbiting their stars at close range, reaching scorching heats and slowly losing their outer layers of gas to their parent star. Why hasn’t Jupiter become a hot-jupiter-type-planet? Truth is, we believe it almost did. After its formation, Jupiter started spiraling towards the Sun bulldozing the hundreds to thousands of inner solar system planetesimals, pushing them into collision between each other, our parent star or in a slingshot out of the system. In fact, it is one of the main explanations to why a star the size of our Sun has only four, fairly small terrestrial planets, when red dwarfs, like Proxima Centauri are far richer in terrestrial mass orbiting them.

What made Jupiter stop spiraling towards the Sun? Saturn!

The formation of a second massive gas giant in our solar system hit the brakes on Jupiter’s fast evolution into a planet doomed to orbit our star in proximity, to be slowly depleted of its gas layers. By this point, the inner solar system was still populated by planetesimals with eccentric orbits, in collision with one another. There are no similarities between the order we know of today and the beginnings of a system full of debris that was still violently evolving towards the final formation of the current planets.

There are no certainties to where exactly the third gas planet was formed, but there are some physical traits to give us a clue. After Saturn, Neptune, the third gaseous planet, was born, followed by the fourth and final gas planet, Uranus. It’s highly probable that the formation of Neptune took place between the current orbits of Saturn and Jupiter. We do know that Uranus and Neptune took almost a billion years to form and caused some major cosmic commotion that would lead you to be able to read about- and understand the secrets of the Universe.

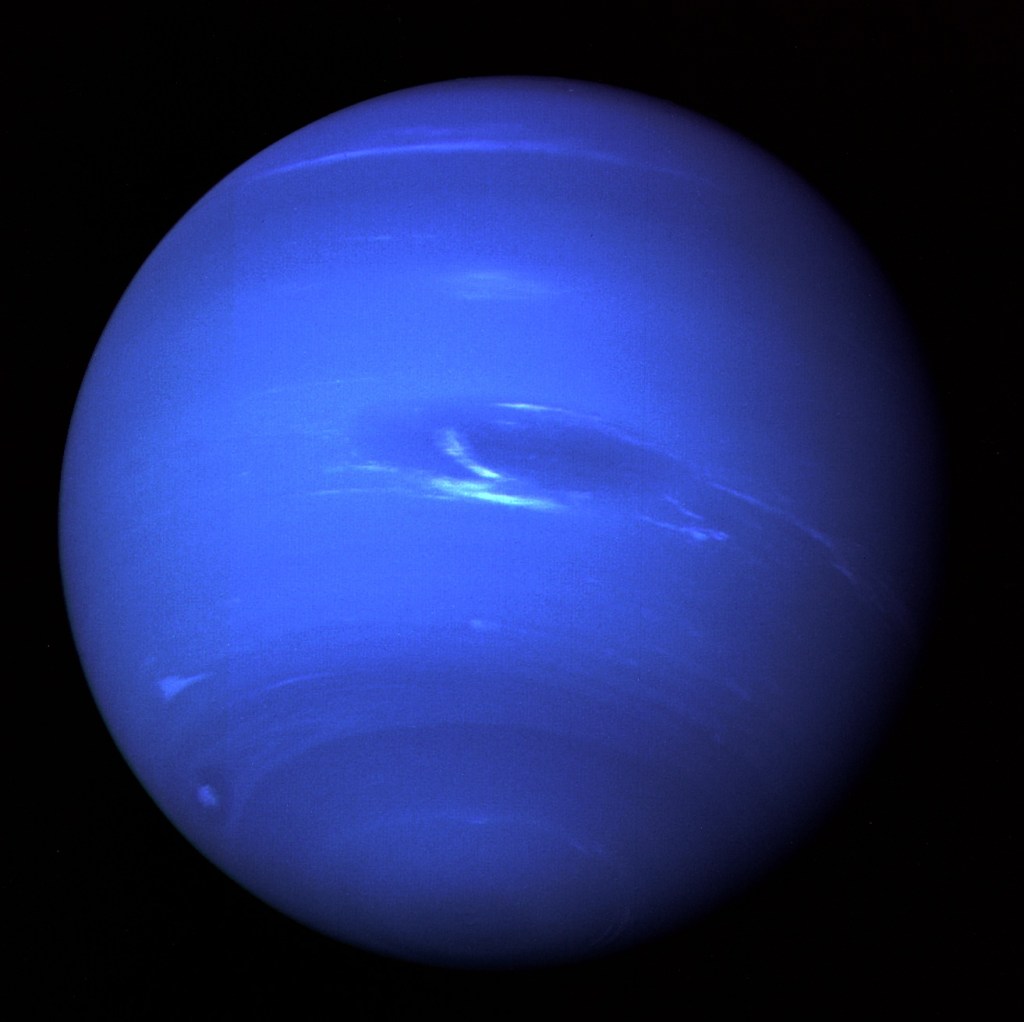

Neptune

Due to the eccentricity of its orbit and the gravitational pull of Saturn on Jupiter, Neptune slowly moved past the orbit of Uranus, rushing like a cosmic bully into the giant ring of cosmic debris of asteroids and dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt, pushing some of these objects towards the inner solar system, causing the late heavy bombardment, with cataclysmic consequences on the inner planets and one consequence that stands out above all: life. In fact, the earliest signs of life on our planet appear right after the late heavy bombardment. We still don’t know if it initially appeared on Earth around our oceans’ thermal vents, or by panspermia, from an asteroid originated out of the crust of Mars, dislocated by the late heavy bombardment. There is however a pretty high probability that this cataclysmic event, generated by Neptune’s orbit pushing into the Kuiper Belt, to have triggered the first spark of bacterial life forms on our planet, around 4-3.7 billion years ago.

It is clear that Neptune formed before Uranus, with an orbit closer to the Sun than the initial orbit of Uranus. Two reasons: mass and density. Neptune is smaller in volume than Uranus, but 20% larger in mass and almost a third denser. It could only have formed closer to the Sun than Uranus, in an area richer in heavier elements. When a star is born, its ignition leaves behind gas and heavier elements. The latter is larger in mass and will remain closer to the star and eventually create terrestrial planets. The remaining gas is lighter and will be pushed farther away to create gas planets. The larger the distance to the star, the less dense the gas planet will be.

Neptune is today the farthest planet in our solar system, yet it is more than twice as dense as Saturn and by a third denser than Uranus, therefore, its initial position was much closer to the Sun, well inside the orbit of Uranus. The high eccentricity of Neptune’s orbit and the gravitational influence of Uranus, Saturn, and Jupiter stabilizing into their final trajectories, pushed the blue ice giant into the far reaches of the planetary system.

Triton

Besides wreaking havoc in the Kuiper Belt and displacing asteroids and comets towards the inner solar system into the late heavy bombardment, Neptune also acquired a new moon. Not its own naturally formed moon, but a dwarf planet, Triton, dislocated from the sterile waste of the far reaches of the solar system, right into the orbit of the ice giant. And Triton, just as his newly acquired parent, became a bully on its own, displacing and crushing into the many natural moons of Neptune, thus becoming king over the frozen turbulent atmosphere of the ice giant, accompanied by the surviving 13 other moons (that we know of), too small in comparison to the dwarf planet, turned natural satellite.

Among all major moons in our system, Triton is unique. It acts like a moon, though it originated as a different type of cosmic object, with no link to the formation or the chemical composition of the ice giant it has been orbiting for the past 3.5 to 3.8 billion years. Triton is also the only major moon in the solar system with a retrograde rotation, meaning it spins the opposite way in relation to the parent planet’s spin around its own axis. It does, however, take a while for Triton to do a full spin around Neptune; almost seven centuries, or 678 years, to be exact.

Just like its parent companion, Triton is a frozen world. Yet, unlike Neptune, a gaseous and extremely turbulent planet, Triton is covered by a thick icy shell and a significant layer of liquid water enveloping a rocky core. The Sun, 4.5 billion km (30AU) away, or thirty times more distant from our parent star than Earth is, appears as a dim glow above this frozen world. Light from the Sun can barely reach the orbit of Neptune and the icy crust on its moon. Surface temperatures reach -238C, therefore it might be reasonable to assume Triton cannot maintain an atmosphere. And yet, it does! During the 1989 Voyager 2 flyby – the only time a man-made object flew close to Triton – the space probe took a series of pictures of the moon and captured a thin haze of nitrogen atmosphere, visible against the dim light from the Sun.

Artistic impression of Neptune viewed from Triton’s surface

So why is there liquid water on a moon so cold, so deprived of light, orbiting the very last ice giant in the solar system?

Radioactive decay. Triton has a mass far larger than all other moons that smaller in volume in the entire solar system combined. Quite impressive, if we consider it is the seventh-largest moon out of more than 200 moons orbiting the planets of our solar system. Being a fairly young object with a rocky core, the radioactive decay combined with the tidal forces exerted by Neptune’s gravitational influence keep Triton geologically active and alive. Just like Pluto, Triton’s surface is full of valleys and ridges, some of which are newly formed. The chemical composition and the large volume of water also make Triton a very likely candidate to host primitive life forms beneath its crust, in the vast, pitch black underworld ocean.

Yet, there is a downside when you orbit an ice giant in retrograde motion. Being tidally locked to Neptune, Triton is also decelerating, forcing it to spin inwards towards the parent planet. Being much closer to Neptune (354,000 km) than the Moon is to Earth (384,400 km), Triton will reach a point in its inward spiraling – around 3.6 billion years from now – where it will be pulled apart and destroyed by its parent planet, disintegrating into an impressive ring system around the ice giant.

By the time Triton will meet its demise, the Sun’s luminosity will have increased by 50% making the Earth a scorching hell and Mars too hot to still be Earth 2.0. Around the radiation of an ever aging and expanding Sun, another moon in the solar system might become the hospitable alternative for life as we know it to thrive: Saturn’s own Titan.

— Roman Alexander

A word from the author:

Since this article is the first out of a series dedicated to the moons in our solar system, I felt the need to write a somewhat more detailed introduction into the beginning of our cosmic neighborhood, since it might shed some light on the evolution of the planets, their orbits, and the formation of their natural satellites.

Leave a comment