As we venture further into our Planet’s past, the quest for reconstructing key events tends to become ever so difficult and debatable. We rely on geological strata, fossils and chemical composition to uncover the narrative of life on Earth and the perils that have risen in its path.

Besides the five major extinction events during the Paleozoic Era, there were several other calamities that have shaped Earth’s biodiversity to a lesser extent. Unlike the occurring events in our day and age, when humans are the main culprit for possible disaster, it is common knowledge that life on Earth would have thrived harmoniously for the past, almost four eons, if not for volcanism, cosmic impactors, earthquakes or tectonic shifts.

But is common knowledge even true? Has life never posed a threat to itself until the homo sapiens? The first mass extinction (approximately 443 to 440 million years ago) is maybe the most evocative illustration that would beg to differ.

Barren Lands

For eons life on Earth remained fairly simple with little to no diversification. Uni- and some simple multicellular organisms inhabited the oceans of our Planet; sometimes solitarily, other times in small colonies, yet nothing revolutionary and pointing towards the biological complexity as we know it happened. As the Proterozoic Eon was coming to an end, our silent Blue Marble was finally ready to embrace the clamor of being animated by life.

And thus came The Cambrian (538.8 to 458,4 mya).

Single-celled organisms living in colonies took on defensive roles to protect the inner-most cells, that would no longer need to prioritize their own safeguard and could now specialize in various processes. Complex organisms emerged, the Phanerozoic Eon (our current eon) began and The Cambrian Explosion, lasting around 20 million years (starting 538.8 mya) filled the oceans with an abundance of animals: from trilobites to sponges and molluscs, from crustaceans to the very first primitive vertebrates. Animals were still very small in size, and a peculiar sight to witness, such as the Anomalocaris (probably the largest animal and top-predator on the planet during those times, although, no larger than an otter), the abundant Marrella (an arthropod smaller than a human thumb) or the very strange looking Opabinia, that could reach the “staggering” length of a human’s index finger.

And while the seas were booming with life, exposed land remained lifeless and barren.

After the first 20 to 25 million years into The Cambrian, diversification slowed down. The climate remained warm and humid, but intense volcanism and rapid tectonic movement had already started creating all the prerequisites for the second geologic period of the Paleozoic Era: The Ordovician (485.4 to 443.8 mya).

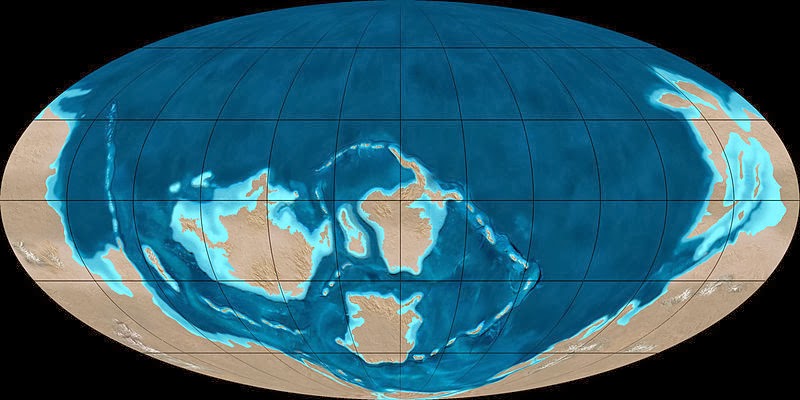

In the beginning of The Ordovician, surface water temperatures of the ocean were around 42°C. To the West, the huge continent of Gondwana – spanning from the South Pole all the way to the Tropic of Cancer – continued rotating towards the equator, but started dissipating into several large archipelagos, such as parts of today’s North and South China, dispersed from the northern hemisphere, to below the Antarctic polar circle. The smaller Laurentia (comprised of most of North America), to the East, shifted all the way to the equator, leaving the Iapetus and the Paleo-Tethys Oceans in-between the land masses; with the rest of the planet, and nearly all of the northern hemisphere, almost completely submerged under the Panthalassic Ocean. Due to the warm temperatures, continents were surrounded by extensive shallow flat sea beds. The result: the greatest proliferation of marine life ever witnessed on Earth, second only to The Cambrian Explosion.

Life Conquers Land. Life Destroys Life.

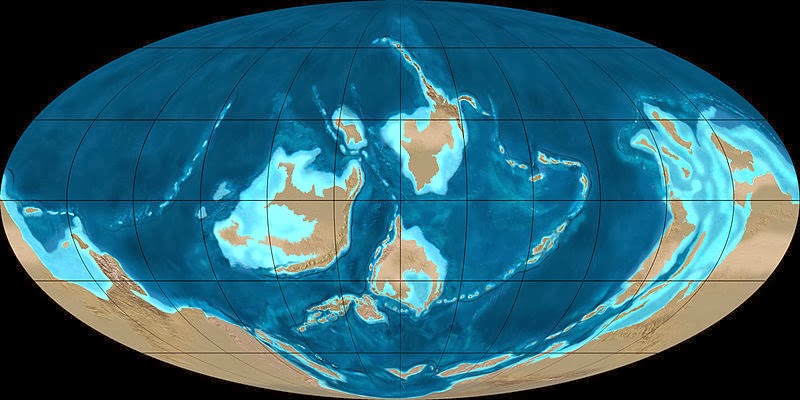

Though very warm during Early Ordovician, ocean temperatures perpetually dropped during the next 40 million years. Planetary climate cooled, ocean levels radically dropped, while icecaps gradually covered and thickened on land. By the end of The Ordovician, the once thriving marine habitats of the flat sea beds were left exposed, killing all species that were relying on these living conditions. The Ordovician-Silurian Extinction had begun, and it was so severe, that it would only be surpassed by the Permian-Triassic Extinction (252 to 250 mya), two hundred million years later.

Contrary to logical and/or geological beliefs, this particular major extinction pulse was very likely triggered by life itself. The very first land plants, to be exact.

Now, along the previous paragraphs I have stated several times that continents were lifeless and barren. More or less! …or better yet, not so much. There were several cyanobacteria present in both sea and on land, and for eons, there was nothing else governing life exposed under the Archean and Proterozoic skies. Based on DNA-evolution, some scientists have argued that plants started migrating on land during mid-Cambrian. There is however little to no testimony to the veracity of such development, except for fossilized plant spores, that would only appear tens of millions of years later during late Early Ordovician, early Middle Ordovician.

When plants started to conquer the land, they were nothing similar to modern plants. They lacked a root-, as well as a vascular system, they were very small in size, resembling colonies of moss hinging on rocks near the shores of the oceans, releasing their spores in the shallow waters that would then transport these spores on other shores, little by little, all around the habitable coasts of our planet.

Unlike water plants, spores from land plants required a thick covering to survive their dissemination and environmental desiccation. Fortunately enough, their thick covering allowed them to fossilize, giving us the needed proof of their very existence.

We have to remember that life had to adapt to our planet’s chemistry and vice versa.

Moving further away from Earth, 1 Astronomical Unit, to be exact, we reach the Sun. Though already eons into its main-sequence phase, our parent star was dimmer 480 million years ago than it is today. As such, global temperatures should have also been far below current ones. Yet Earth was nothing alike the planet we inhabit now. CO2 atmospheric concentration was 14 to 16 times higher compared to the current 0.04%; reaching 5600 to 6400 ppm (parts per million), compared to the 400 ppm in today’s atmosphere. The chemical balance of the greenhouse gas and a dimmer sun led to warmer oceans and a warm climate. But even CO2 needs some help to stay present in the atmosphere, and 460 mya there were no humans around to burn as much fossil fuel as possible to maintain high CO2 levels. Thus, with the expansion of plants on land, CO2 levels began to drop, though not why you might think they did…

When plants emerged from the sea, they hinged on rocks. The arid and barren lands were sterile from the minerals and chemical elements necessary to sustain life, and since plants need phosphorus to survive, they started slowly breaking down rocks to release it. Normally, due to weather, humidity, friction, and several other factors, rocks go through a process of natural degradation, thus releasing phosphorus on their own, which is then transported over time back into the oceans. Plants hinging on rocks degrade their habitats much faster, releasing 50 to 70 times more phosphorus, that is then transported by rain, waves, tides and other water movement back into the ocean. Since algae also thrive on phosphorus, once the first terrestrial plants started depleting the rocks, phosphorus suddenly became abundant, resulting in algae flourishing in the oceans. After the algae bloomed, bacteria started decomposing it, and to do so it needed large amounts of soluble oxygen, therefore depleting the oceans and turning them hypoxic. Since marine life needs soluble oxygen to breath underwater, the long chain of consequences initiated be land plants, killed 50 to 60% of genera and almost 90% of all species.

The lack of soluble oxygen in the oceans led to yet another disaster.

Global Ice Age, Volcanism and Gamma Rays

There is very little to rely on as proof to what happened almost half an eon ago on our planet. Except for geology and fossils, we have close to nothing to base our theories on. We can however sustain some scientific explanations grounded on these factors alone. To name plants as the main culprit of our world’s first mass extinction isn’t as farfetched as one would be inclined to believe.

As mentioned before, The Ordovician saw a constant fall in ocean and global temperatures, leading towards a glacial age. Plants consumed the rocks they were living on, releasing phosphorus into the oceans, that was then processed by blooming algae, that flourished everywhere. After its blooming stage, algae died and was decomposed by bacteria, that needed soluble oxygen from the ocean to break down the algae. Once the oceans were depleted from soluble oxygen, carbon could no longer bind with it to be released back into the atmosphere as CO2, instead carbon sank to the ocean floor, forming large deposits of black shale sediments. This led to a global massive decrease of atmospheric CO2. And since CO2 acts like a dome, trapping heat in the atmosphere, its continuous shortage led to a global fall in temperatures. Furthermore, ever since The Cambrian, continents were moving rapidly, and they never stopped or slowed down during The Ordovician. The constant friction and pressure between continental plates led to the formation of mountain chains, such as the Andes, that appeared during this geologic period. However, when plates collide and are pushed against each other, the immediate result is the high increase of volcanic activity, that thrived during the Ordovician, releasing gas clouds, blocking sunlight and thus cooling the planet even more. Silicate rocks formed from the volcanic activity started breaking down and as a result drew even more CO2 out of the atmosphere.

There was probably also a gamma ray burst that hit our planet during Late Ordovician. A massive star, 6000 light years away, blew into a hypernova, releasing ten times more energy than a supernova. The shock wave of these hypernovas are so energetic that they can break entire worlds and even stars apart. Presumably, the gamma ray burst stripped much of Earth’s ozone layer instantly, leaving land life, marine plants and shallow water animals exposed to extreme cosmic radiation, leading to immediate death. This theory would explain why life living in shallow waters was most affected by the extinction event, as the oxygen depletion caused by plants should have affected it far less than deep-water life. Nevertheless, not all ozone layer was stripped off, therefore it didn’t affect life everywhere. Though the hypernova theory stands, the ozone layer couldn’t have represented an extinction pulse by itself. But there is another particularity of the ozone layer. It is a greenhouse gas, that once dissociated, leads oxygen to bind with nitrogen to form nitrogen dioxide (NO2), an aerosol that would have contributed to the further cooling of the planet.

And yet, both plants and animals adapted to cooler climates. Marine life became more resilient and, in order to survive, was forced to explore new territories, the same ones where pioneering plants had now diversified, evolved and were starting to develop roots and vascular systems, moving further away from the oceans, thus conquering the land. The Ordovician was over, but life moved into The Silurian stronger than ever before.

Regardless of all the causes that led to The Ordovician Extinction Event, there was no other way for life to continue its quest to conquer both sea and land.

Earth is a huge asteroid. It is vibrating with energy, but this energy is physics, not life. Our planet, isn’t special because it’s blue, covered by oceans, or orbited by the Moon. True, these are all essential, but inanimate factors, whatsoever. Our planet is special because life has thrived, diversified, evolved and reshaped everything on it; writing a plenitude of musical notes over its monotonous sounds. Life revolutionized Earth’s chemical surface balance, transforming a barren rock into a fertile home, turning a lifeless blue asteroid into a Blue Marvel.

– Roman Alexander

Leave a comment