The beginnings of the Solar System witnessed some haphazard events in the formation of the protoplanets out of the space debris left behind after the ignition of our star. Tens of rocky planetesimals revolving around the Sun started colliding against each other; others were pushed towards the star by a young Jupiter, spiraling ever closer inwards to the Sun, while some were completely slingshot into the intragalactic space due the gravitational influence from the same Gas Giant.

Instead of having several, more massive rocky planets orbiting the Sun, our system was almost depleted of every solid planet, by the newly formed gas giant, destined to become a hot jupiter we so often discover revolving in close proximity to other stars. Yet the spiraling mayhem stopped, Saturn began coalescing, thus pulling Jupiter back into a wider orbit around the Sun. Mathematically speaking, the gravitational pull of Saturn on Jupiter could not suffice into determining such revolutionary displacements. Something had to influence Saturn as well into preventing it to follow the same path as the first gas giant. This something was not one but two newly formed planets: the ice giants, Neptune and Uranus.

When a new system is born, the ignition of its star leaves behind both solid and gaseous debris. In most cases we know of, the remaining gas is more than enough to form a second star (binary system), even a third. Just think about our closest neighbor, the Alpha Centauri System, dominated by two sun-like stars (Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B) and the much more popular red dwarf: Alpha Centauri C, also known as Proxima Centauri.

Solar nebula – Artistic impression of our proto-Solar System

Our Solar System should not have been that different. More so, considering the general pattern of star systems in the Milky Way, our own is indeed the odd one out with one sole star. Simply put, there was just not enough hydrogen gas for a binary system. The leftovers were taken mostly by Jupiter, then Saturn, with Neptune and Uranus vacuuming the remaining hydrogen and helium gas, icy water and other debris left in the farther reaches of the system. After the formation of the last two planets – Neptune and Uranus – a string of gravitational pulls was exerted on Jupiter, by pulling it farther away from the Sun and the inner Solar System into its current position. Saturn was also pushed back, triggered by Jupiter’s motion, resulting in the displacement of Neptune’s orbit, in an elliptical elongation of the Planet’s path, far beyond Uranus’ orbit. Thus, Uranus switched places with Neptune from eight to seventh planet from the Sun.

Ice Giants

There are no records to state such motions inside the early solar system, yet there is mathematical evidence to explain the displacement of orbits. Besides the paucity of solid mass in the inner system, the formation of the Moon and the known consequences of the Late Heavy Bombardment (4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago), we have solid data about both ice giants orbiting the planetary outskirts of our cosmic home.

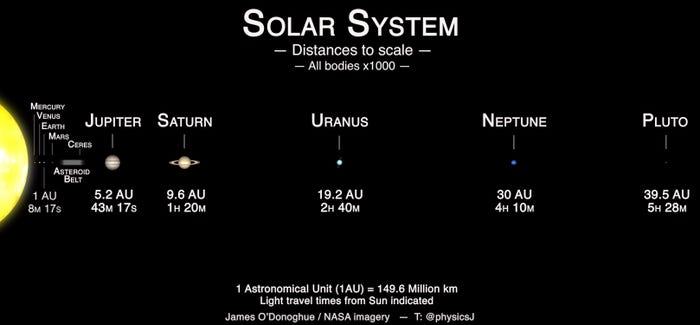

When star systems such as our own form, the farther away the planet from its parent star, the less material it has at its disposal to coalesce. Yet our two ice giants appear to be misplaced. True, Uranus is 63 times larger in volume than Earth, while Neptune is only 57 times larger, but when it comes to mass and density, Neptune is 1.6 gm/cm3 while Uranus is only 1.3 gm/cm3. Same goes for mass: Neptune is 17.1 Earth masses, while Uranus only 14.5. Besides these differences, both planets are too far away from the Sun. Much farther than they should be. Uranus is 19.2AU on average, Neptune is 30.7AU. Consider that 1AU is approximately 150 million km, as in the average distance between the Earth and the Sun. Jupiter is on average 5.2AU (778 million km) and Saturn is 9.5AU (1.443 million km) away from the Sun. Uranus is more than twice as far from the Sun then Saturn is, while Neptune more than three times. In other words, you could fit the entire Solar System till Saturn’s full orbit between the orbits of Saturn and Neptune. It is therefore that the only plausible explanation to date for the orbital displacements and physical characteristics according to position remains the string of gravitational pulls in the early era of our Solar System.

Distance to scale between planets in the Solar System – Photo Credit: Business Insider

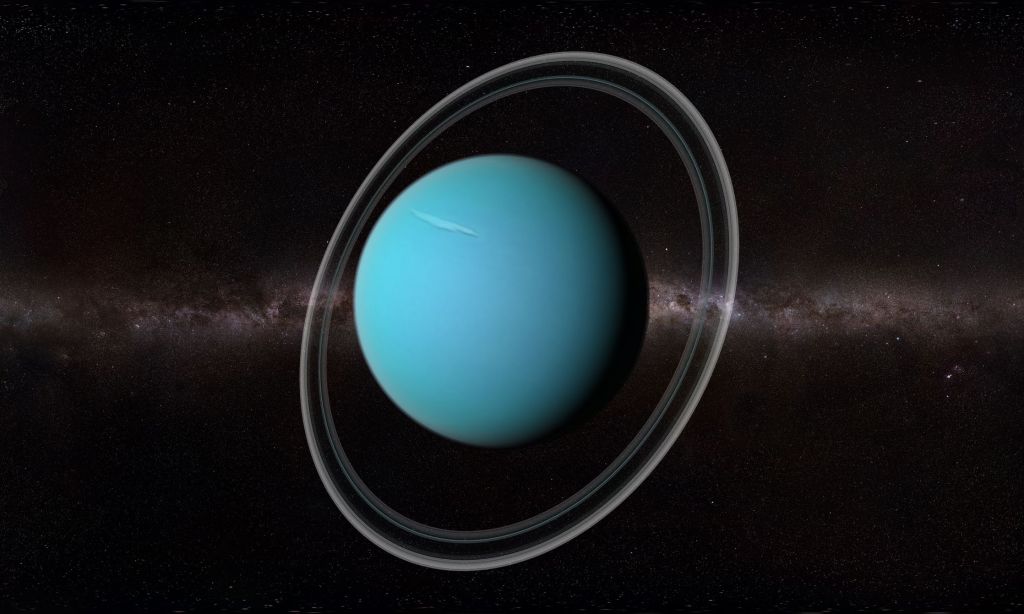

Tilted Giant

Compared to Neptune, Uranus might appear as a bloated ice giant, with more volume but less mass and density. Still, it most probably has far more mass than it originally did.

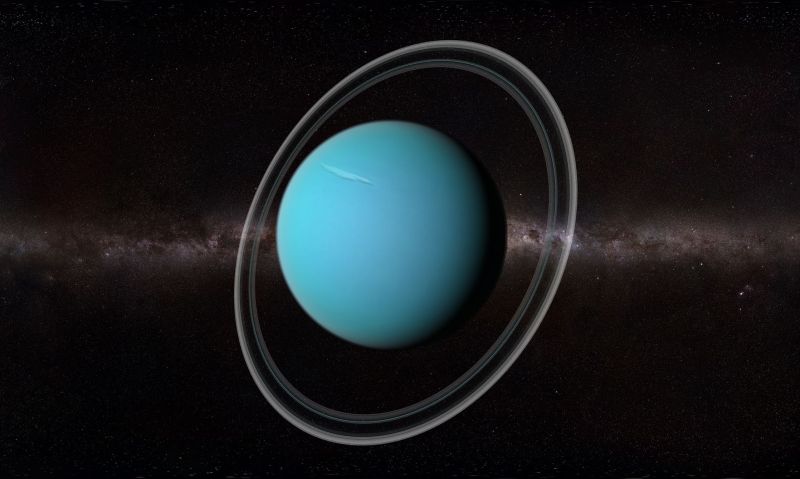

When we take a wide look at the Solar System, we notice the scars left behind by several traumatic events of its past. Venus spins clockwise around its axis, unlike any other planet, due to a heavy collision, possibly during the Late Heavy Bombardment or right before it. Earth’s Moon is the aftermath of Theia’s impact with our Planet. Mars’ Olympus Mons, tallest mountain/volcano in the solar system (21.2 km tall), is a statement of the Red Planet’s last dramatic volcanic activity, that turned Mars into a sterile rock orbiting the Sun (remains to be proven if this is indeed the case, following current and future Mars missions, that will determine if it still has an incandescent core and mantle). Yet Uranus’s axial tilt, highlighted by its rings, is by far the most evident aftermath of a past super collision with another planet or planetesimal.

While all the other planets’ axial tilts range between 0.01⁰ (Mercury) to 28.32⁰ (Neptune), Uranus’s axial tilt is 97.77⁰, making it spin sideways around the Sun, over an 84 year long revolution, with one pole in complete darkness and the other in full sunlight for 42 years each. As an important sidenote, Venus’s axial tilt is 177.3⁰, effectively upside down, therefore appearing similar to the other 6 planets.

Artistic impression of Uranus

We call the last four planets gas giants, denominating the last two as ice giants, due to their composition and surface temperature. Uranus, however, is more peculiar than Neptune, and it might be related to the past super collision with the planet/planetesimal that moved its axis to a 97.77⁰ angle. While the outer and inner atmosphere is made of hydrogen and helium gas, its mantle is a turbulent and incandescent water, ammonia and methane ices ocean, covering an Earth-sized core of mostly silicate minerals, iron- and nickel rock. Due to extreme pressures inside the mantle, methane is broken down into carbon molecules transformed into solid diamonds “raining” toward the core. Because of the high temperature and pressure, the core is enclosed in a liquid diamond ocean with diamond-bergs floating on its hot surface. One of the plausible consequences of Uranus’s composition is its strange magnetic field. Unlike any other planet, and probably due to the deflection caused by the water and ammonia mantle, Uranus has an irregular magnetic field, similar in strength to Earths, though unlike the other planets, it doesn’t emerge from the Ice Giant’s geometric poles, but 59⁰ off. Uranus also reaches the lowest atmosphere temperatures in the solar system (-218⁰C), although Neptune is by 10AU farther away from the Sun. And unlike the other three gas giants, Uranus is far less turbulent, with planetary storms forming only during seasonal changes, spread decades apart, when the poles move from the dark to the bright side of the orbit. It does remain a mystery to why temperatures are always lower at the pole directed towards the Sun, compared to the equator left in a perpetual twilight due to the axial tilt of the planet.

Rings of perpetual destruction

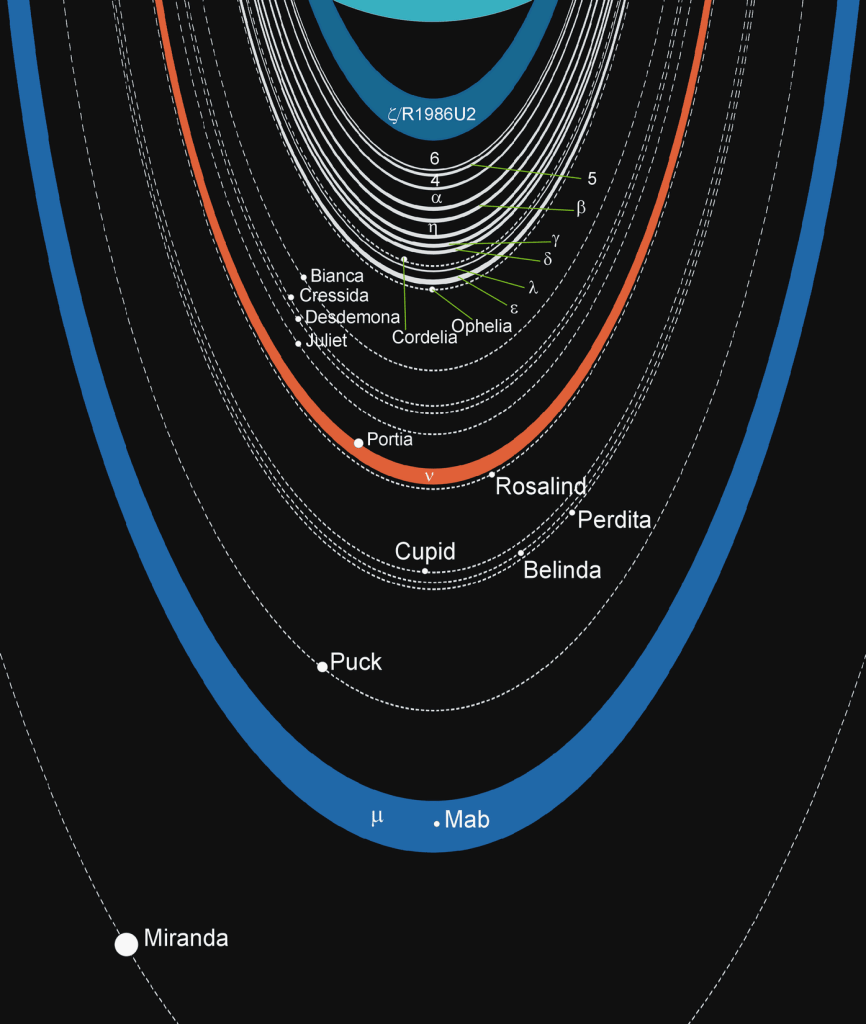

Just like Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune, Uranus has a complex ring system. Unlike Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune, Uranus’s rings are perpendicular on the solar plane, not (almost) on the same level. Thanks to Voyager 2 (local flyby in 1986) and the Hubble Space Telescope (in 2005), we know Uranus has 13 distinctive rings, with 11 close to each other and divided by shepherd moons, an 2 more rings, twice as far away from the planet as the eleventh ring. The ring system was the second one to be discovered (right after Saturn’s) and is also the second most complex, compared to all gas planets. It is also a very unstable system (as most ring systems are), with shepherd moons and asteroids forming, then colliding with each other, into a perpetual cycle of creation and destruction. Only a few kilometers wide and very low in density, Uranus acquired its rings millions to billion years after its formation, and will eventually consume most of the containing matter due to gravitational pull and collision with the planet.

Uranian rings

The 27 discovered moons of Uranus are mostly sterile rocks, though beautifully named after characters from William Shakespeare’s (26 moons) and Alexander Pope’s (1 moon) plays. Only Miranda, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel and Titania have reached hydrostatic equilibrium, with a maximum diameter of 1578km for Titania to a 472km diameter for Miranda. The rest are irregularly shaped moons, just like Mars’s Phobos and Deimos.

All five major moons are heavily cratered and very dark. They also spin the same as their parent planet, with an axial tilt very similar to Uranus’, with one pole completely in darkness for 42 years, and the other in full sunlight for 42. Titania, Uranus’s largest moon, is only the eight largest in the Solar System, and just like the other 4, completely lacks atmosphere. All five major moons are made out of rock and ices, with a thin possibility for Oberon and Titania (the two largest) to have a liquid ocean between the rocky core and the rocky surface. To speculate that there might be a possibility for single-celled life inside these oceans, would be a far reach. Unlike other moon/planet systems, such as: Titan/Saturn, Io/Jupiter, Europa/Jupiter, Triton/Neptune, Uranus’s major moons are far too small, too cold and too deprived of a strong pressure on their cores from the planet’s gravitational influence, in order to maintain water temperatures that could allow life in any form to emerge.

Major moons

Every single planet in the Solar System was named after a Roman god. Every planet except Uranus, and just like the Greek god of the skies, the light blue haze of the ice giant encloses so many questions yet to be answered to, so much of its past, present and future left to be discovered.

– Roman Alexander

Leave a comment