Every year, our night skies offer us remarkable spectacles of “shooting stars”, harmless interactions of meteoroids with our stratosphere, turned to meteor showers. By the end of every year, the cold Northern Hemisphere nights are lit by the Quadrantids, cosmic augurs for the dawn of a new year to come.

Though not the most spectacular, nor the most visible, the Quadrantids (visible each year from December 28 to January 12) offer an evocative insight into the evolution of cosmic bodies transitioning our solar system. Being a seasonal occurrence throughout our entire lives, we tend to ignore any relation to previous events or stages of development to present state of existence of said Quadrantids populating a cosmic perimeter close to Earth’s orbit.

————–

China, 1490, early spring: a sudden airburst, similar to the Tunguska airburst in 1908, hits the Shaanxi Province, killing thousands. Several sources indicate a shower of rocks, though there are no official records during the Ming Dynasty of such an event, only recounts in local documents and gazettes, describing the objects to be as large as “goose eggs”. The alternative culprit is a hail storm, though very unlikely to happen in late March, early April, and even so, it wouldn’t explain why the population of an entire city felt the need to fled during and following the event, nor does it explain the supposed number of 10.000 casualties. Coincidently, there are official records from the same year for a newly discovered comet, C/1490 Y1, identified by several other astronomers in Eastern Asia, including: Japanese, Korean and Chinese.

Studying the orbit around the Sun of Comet C/1490 Y1 led to the mathematical conclusion, that it had disintegrated near Earth’s orbit, leaving a 2.6 to 4km diameter Asteroid 2003 EH1, to circle our star in an elliptical full orbit of 5.52 years. Part of the initial comet probably entered Earth’s stratosphere in 1490, where it disintegrated into smaller rocky objects, previously held together by C/1490 Y1’s ice. With each orbital cycle the Comet lost all of its volatile ices, when it plummeted towards the Sun. The only traces left by the initial C/1490 Y1 are the late-December/early-January Quadrantids and Asteroid 2003 EH1, as the severed parent of our winter skies’ annual meteor shower.

Living on a planet with no imminent cosmic threats to disrupt our daily routine, we sometimes fail to acknowledge the perpetual transit of several objects throughout our solar system. We tend to look at our cosmic neighborhood as a horizontal layer of planetary orbits in constant revolution around the Sun. Truth is, we don’t just live in the goldilocks of our galaxy and in the goldilocks of our solar system, we also live during a temporal goldilocks, where the Sun and surrounding planets have already had their fair share of bombardments, long before complex life had evolved on Earth. Still, there are asteroids and comets, most following specific elliptical orbits around our star, while some – like the ‘Oumuamua object – with no relation to the Oort Cloud or the Kuiper Belt, home of most homeland cosmic bodies.

Following the general rule, C/1490 Y1 originated in the Oort Cloud – far border of the solar system – too wide spread and with a total mass far too low to coalesce into a planet. Like most comets, C/1490 Y1 was probably disrupted from its original position by a larger object or cosmic event, that sent it rushing towards the Sun. The orbits of such objects, though not as regular and predictable as for the 8 planets, do follow mathematical patterns, allowing us to calculate certain possible dates of collision with Earth, given the two bodies would come too close in their orbital positions. Yet for all comets, each revolution is a step closer towards a full decay or transition into an asteroid. C/1490 Y1 saw its own demise in late-March or early-April 1490, when a large part of the rocky material separated from the original comet. Some of this material became space debris populating the proximity of Earth’s orbit, while the rest rushed against Earth’s atmosphere, disintegrating into pieces, thus causing the Shaanxi event. The remaining ice of C/1490 Y1 was eventually lost with each cycle around the Sun, until C/1490 Y1 seized to exist, leaving only Asteroid 2003 EH1, behind, as the rocky core of the former comet.

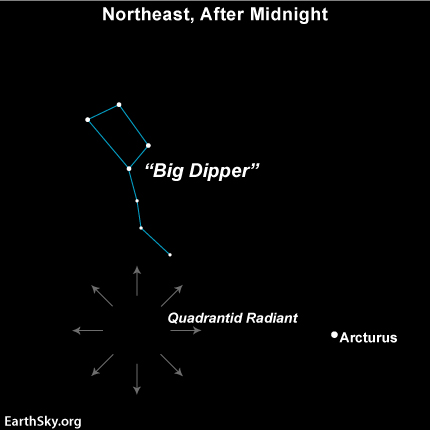

Quadrantids’ location in the early-night to after midnight sky every January 3-4. Source: Earthsky.org

Since the debris left behind by the now-defunct-but-turned-to-asteroid-Comet is far too small to be observed from Earth, we have no clear prevision as for how many years to come we can still enjoy the Quadrantids in January. We do know that there is virtually no chance of Asteroid 2003 EH1 to hit Earth during the next tens of thousands of years.

In the meantime, Earth’s gravitation will continue to sweep the surroundings of its orbit, attracting meteoroids, thus turning them to meteor showers as a reminder of lost or decayed cosmic wanderers that have left the darkness of the Oort Cloud into a crumbling spiral around our parent star.

— Roman Alexander

(This article is dedicated to Mrs. Ana-Maria Roman)

Meteor Shower Calendar:

The next Quadrantids Meteor Shower will reach its peak on January 3-4, 2022.

The best time to observe the phenomenon is soon after nightfall till after midnight, when you can observe up to 80 meteors an hour.

The best place to find them is south of the lowest star in the Big Dipper/Ursa Major.

For each four-year cycle the peak is reached on January 3-4, except for the one right before the leap year, when the peak is reached on January 4-5 (i.e., 2023, 2027,2031 etc.).

Leave a comment