R Leporis and other carbon stars

Ever wondered why the Sun appears red on the sunset? On the visible to the human eye light spectrum, when the Sun is above us in the sky, light has to travel a shorter distance through Earth’s atmosphere to reach our retina. The short wavelength high frequency part of the spectrum is able to reach us, corroborating our sensitivity to blue frequencies scattered and deflected several times, resulting in the blue skies we see. The sun, emitting light of mostly yellow frequencies, also appears to us yellow when it is above us in the sky.

As the day fades away and the horizon gets closer to the solar disc, light has to travel more through the atmosphere to reach us. Blue shorter wavelengths are scattered by particles and water droplets in the atmosphere, while low frequency long wavelengths of yellow and red are the ones to reach our eyes, making the Sun turn from orange to red and the sky from blue to yellow to orange to red.

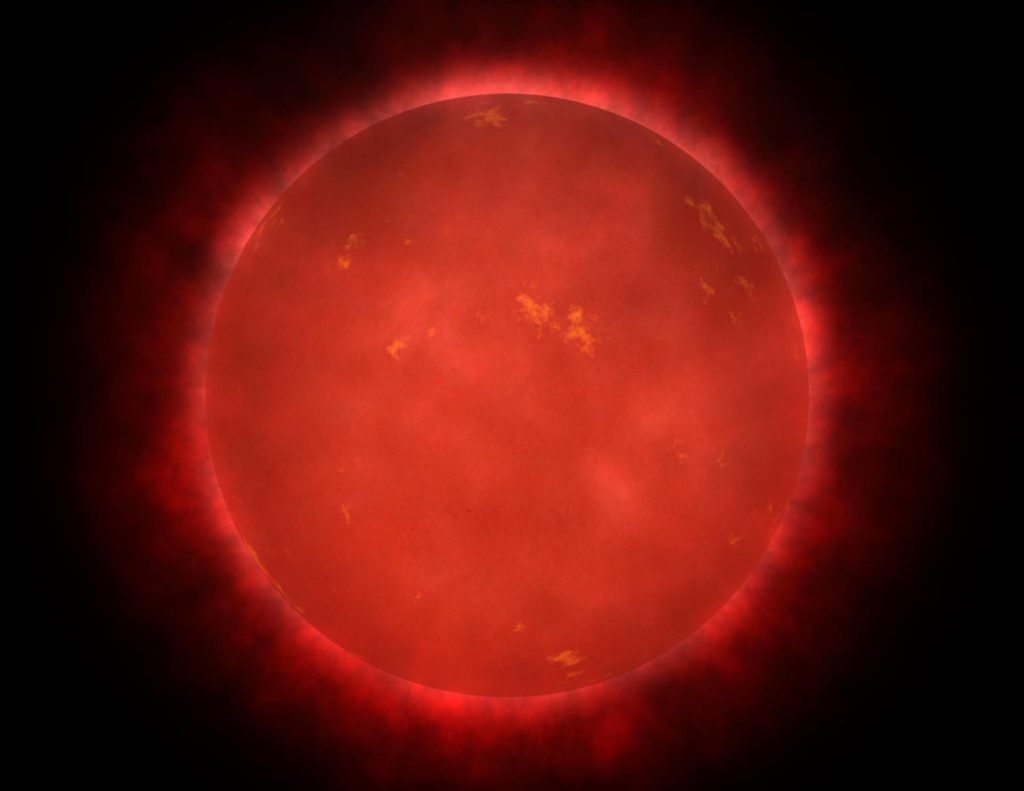

When it comes to carbon stars, the idea is somewhat the same. Radiation generated by the stars in the form of light should normally be white. However, the term normal and the Universe don’t go well together, as the first will never apply to the latter. High amounts of carbon in the atmosphere of these carbon stars (C-type stars) will make them appear red or ember when observed by humans through telescopes. Indeed, most of these stars are too faint for us to be observed by the naked eye, but rather with the help of telescopes.

What are carbon stars and, more importantly, will the Sun ever become one?

Most, if not all, carbon stars we have ever discovered turned out to be variable stars. Internal or external forces make them change their magnitude. They expand or contract, change shape from a sphere to a non-spherical object, they pulsate from a couple of times a day (short pulsating stars that fit the description of carbon stars) to one time over several years (some carbon stars, such as R Leporis, can also fit into this category), decades or centuries. A good example is Betelgeuse or a closer to home cosmic monster/menace, Eta Carinæ (none of which are, nor fit the short pulsating definition of carbon stars). Some stars only vary one time in their entire existence. You all know about this cataclysmic variability: it’s called a supernova, caused by the outward pressure overtaking the inward pressure. The Sun doesn’t fit in any variable star category. It is a balanced main-sequence star where the inward pressure counterparts the outward pressure. By the end of its main-sequence stage, it will just bloat into a red giant, losing layers of hydrogen and helium, leaving a planetary nebula as a dim reminder of its existence.

There is a good reason why carbon stars have a carbon-rich atmosphere: they are usually red giants.

Stars are ever exploding bombs, continuously fusing atomic elements and releasing radiation. For most of their lives, they fuse hydrogen into helium. When they run out of hydrogen, the outward pressure overruns the inward pressure, and they start to bloat, turning into giants. However, running out of hydrogen is not a death sentence for a star, as it continues to fuse helium into heavier elements, thus three He atoms merge into a Carbon atom, four He atoms merge into an Oxygen atom.

The large majority of dying stars we have observed so far have atmospheres richer in Oxygen. Those where Carbon atoms exceed Oxygen atoms, are carbon stars. Those where Carbon and Oxygen are in equal amounts, will become rich in Carbon Monoxide molecules and eventually turn into carbon stars as well. This entire process is mainly generated by the variability of these short pulsating stars.

C-type stars were discovered more than a century and a half ago by an Italian Catholic priest, named Angelo Secchi, head of the Pontifical Observatory in Rome, we have known about their existance for a long time now.

One of the most intriguing examples is R Leporis, 1347 light years away from Earth, with a variability period of approximate 444 days and a radius at least 400 times greater than the Sun’s. Though it might seem impressive, R Leporis might only have 2 to 2.5 times the mass of the Sun. Considering our own star will bloat to have a radius at least 150 times of its current one, a dying star such as R Leporis being so large in volume fits the general evolution of red giants.

There are two theories surrounding this particular star. Both of them agree that R Leporis is in its final stage of a bloated dying star. The first, more accepted theory, is that the R Leporis is about to lose its outer layers and turn into a planetary nebula, dimming away into eternity. The second theory is the “vampire star”, where R Leporis is exerting a gravitational pull on a nearby star, sucking away the outer layers of hydrogen gas, thus rejuvenating itself. There are several observed cases of these vampire dying stars, usually depleting the rich outer layers of hydrogen of larger stars nearby. These second theory involving R Leporis is, however, pretty recent, therefore it remains to be scientifically proven through observations.

Are carbon stars a threat to us? Not at all! Are variable stars a threat to us? Remember Eta Carinæ, the luminous blue variable monster of at least two stars conjoined, of 200 solar masses, lurking in the center of the Carina Nebula? She might be! But at least not for the next 7500 years. – Roman Alexander

Leave a comment