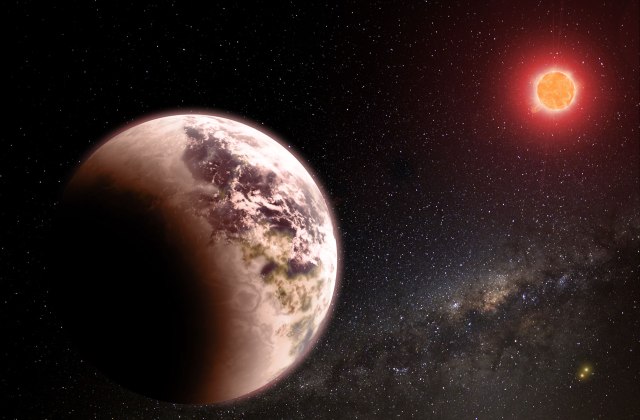

The day I turned 32, on August 24, 2016, I got an unexpected, yet spectacular gift as it was announced that the hypothesized existence of an Earth-like planet orbiting Proxima Centauri had become an astronomical certainty. The knowledge of an exoplanet very similar in diameter and mass to our own spiked the imagination of the entire astronomical community, opening up the possibilities of the presence of life as close to home as possible, as Proxima Centauri is indeed the closest star to the Sun, at a 4.2 ly distance.

For a while, all data pointed towards Proxima b being a trustworthy candidate for hosting life, as it is a rocky planet with a metallic core (with a probability of ≤90%) and a mass between 1.27 to 3 Earth masses, orbiting its star in the habitable zone during an 11-day period on an orbital eccentricity lower than 0.35. A couple of months after it was confirmed as an exoplanet, the French National Center for Scientific Research hypothesized the existence of liquid water oceans on Proxima b’s surface and an atmosphere similar to our planet’s. However, Proxima Centauri is nowhere similar to our own star and Proxima b is catastrophically different from our own planet.

The Sun is a yellow dwarf, a G-type main-sequence star, converting hydrogen gas into helium through nuclear fusion in its core. Sun-like stars are the most stable stars in our Galaxy, fusing hydrogen in their cores for 10 to 11 billion years when they become red giants that eventually lose the upper layers of hydrogen gas and turn into white dwarf surrounded by a planetary nebula. During their 10 billion years main-sequence timeframe, these yellow dwarfs, like our Sun, if surrounded by rocky planets with magnetic fields, orbiting the star in the habitable zone of the system, can ensure the development and existence of life, granted that all chemical ingredients are present on the planet in orbit.

Proxima Centauri is a different type of star: a red dwarf. It is ten times smaller in diameter than our Sun, eight times smaller in mass and 0,0056% as luminous as the Sun. However, it is 33 times denser than the Sun. For a different perspective, imagine that Proxima Centauri is only 1.5 larger in diameter than Jupiter, though you’d have to squeeze in 129 Jupiters to equal the star’s mass. A star the size of a red dwarf might not seem impressive, its luminosity definitively isn’t, as you cannot see it with the naked eye on our night’s sky here on Earth. Yet, stars like Proxima Centauri burn through their hydrogen fuel not for ten billion years, but for trillions! Red dwarfs are the most resilient stars we know of in the Universe, as they will live to witness the death of all other types of stars we know of today. Some of the reasons are: slow nuclear fusion and the amount of gas at their disposal. The Sun and other Sun-like stars, though eight times larger in mass, can only access 30-35% of their hydrogen fuel, residing in the cores of these G-type main-sequence stars. Furthermore, the volume of the Sun’s core represents only 0,8% of the total volume of the star. After the Sun fuses all its hydrogen fuel in the core, it continues to fuse the helium resulted in the fusion, but will never access the rest of its hydrogen fuel residing in the upper layers. Red dwarfs not only go through their hydrogen fuel at a much slower pace, they are fully convective and can circulate the entire amount of hydrogen at their disposal, hence, their incredible trillion year lives. The Sun is already halfway through its ten billion lifespan; Proxima Centauri is still at the very beginning of its multi-trillion-year lifespan.

We know little about the evolution of red dwarfs throughout their lives, as every single one of these stars that have ever ignited in the entire history of the Universe are still incredibly young compared to their enormous lifespans. What we do know is that stars like Proxima Centauri experience periods of dramatic increase of lightness (most of them lasting for only a couple of minutes), caused by magnetic storms emitting giant flares that could sterilize all planets orbiting it. Another characteristic, applied to Proxima b as well, is that their planetary systems are very short and close in orbit around the star. Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun, averages a distance of 57 million km from the star. Proxima b averages a distance of 7 million km from Proxima Centauri. As a further example, the entire TRAPPIST-1 planetary system (of seven exoplanets) could easily fit inside the orbit of Mercury. As a consequence, Proxima b is tidally locked to its parent star, with one side of the planet always facing the star, thus reaching scorching temperatures, while the other side is always facing away in the dark cosmos, experiencing constant freezing temperatures. We could hope for life in the twilight of the planet, inside the ring of passage between the planet’s constant day and night. However, we know by now that Proxima Centauri is a flare star that has probably already sterilized the planet with radiation, blowing away it’s atmosphere.

We’re still not 100% certain if Proxima b is a barren rock orbiting its star, though all indications lead to it being devoid of any forms of life. As for the future? Who knows! Proxima Centauri is still way too young and temperamental, flare-wise. It might stabilize in the far cosmic future and become the protective and life-giving parent star our Sun is to our Blue Marble. – Roman Alexander

Leave a comment