Before we start talking about individual exoplanets (something I know we all want) let’s clear the path for some basic info about these celestial bodies and the history and methods of their discovery.

According to NASA, we’ve discovered 3838 confirmed bodies and 2899 possible candidates and counting. As for the history of discovering exoplanets (planets outside our solar system), I don’t want to go into details, however, the very first exoplanet was theorized with some evidence in 1917, but failed to be recognized as such. Therefore, we jump from 1917 directly to 1988, when the largest planet orbiting (in a 2.5 year orbit) the star Gamma Cephei ab was discovered and recognized as an exoplanet. Subsequently, in the years to follow the number grew exponentially reaching almost 4000 of confirmed exoplanets, by the end of 2018.

We use different methods in discovering these celestial bodies, although almost all of them inquire indirect approaches, such as transit methods or radial-velocity methods. The reason is: exoplanets are, in fact planets, therefore they do not emit energy, so it’s nearly impossible to detect them in the vastness of space.

Let’s see how these two methods actually work!

The transit method inquires the measuring of the brightness of a star for a specific time-frame. If a planet crosses the disk, the star’s brightness will dim by a certain (and extremely small) percentage. By calculating the size and brightness of the star and the percentage of decrease in luminosity, we can calculate the size of the planet and focus on the star hoping we can detect the halo around the planet when it’s in front of the star’s disk, thus measuring the percentages of chemical elements in its atmosphere.

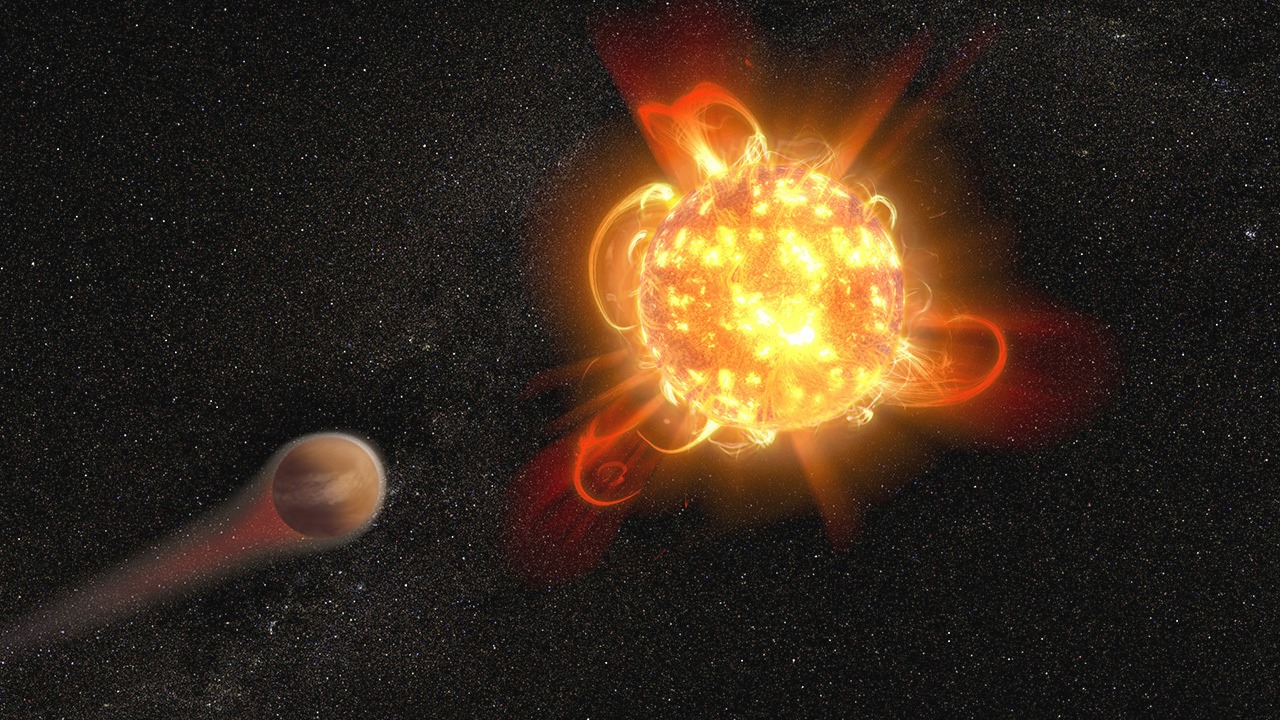

The radial-velocity method, or Doppler spectrometry, is basically the wobble method. We look for wobbly stars, not orbiting around their own center, because such objects are influenced by the planets orbiting them. There is however one major problem with using this method as it’s extremely difficult to detect small Earth or Mars-sized planets this way, because they are just too small to have a major gravitational influence on their parent star. By using the radial-velocity method, we mostly detect Jupiter-sized planets. I know most of you have already heard of hot-jupiters, gas giants orbiting their star in close proximity in a spiraling orbit towards collision. One good example is Osiris (HD 209458 b), discovered in 1999, with an entire year lasting only 3.5 Earth days. Don’t worry; I’ll dedicate an entire article to Osiris, in order for everyone to understand what happens to this gas giants and why they are galloping towards their demise.

By the end of the 20th century, astronomers developed the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) that helps us detect smaller planets, with Draugr (2300 ly away from Earth), discovered in 1994, as the smallest exoplanet to have been discovered to date. (*Draugr is only twice the size of our Moon’s volume)

Today we start on a journey of learning about new and fascinating worlds, residing far outside our solar system. Each article will feature details about methods of discovery, parent stars and cosmic phenomena. As always, if you have a special exoplanet close to your heart, let me know in the comments or in a message. – Roman Alexander

Leave a comment